Theater artist, writer and educator Nell Bang-Jensen believes that instead of staging big shows on a main stage, theater producers might better serve their communities by finding out what people in the community are interested in and engaging them in the artistic process. That’s the idea behind a new work in development at the Pig Iron Theater Company, where Nell is the Associate Artistic Director.

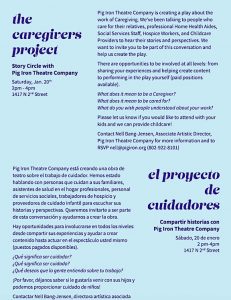

In today’s show she talks about “The Caregiver Project,” a performance piece being shaped by caregivers in the Philadelphia area who are collaborating with Pig Iron, sharing their experiences with care and helping to create a show that opens in June. Nell also talks about her first real exposure to end-of-life issues through the hospice journeys of her Danish grandparents, what she hopes the audience will take away from “The Caregiver Project” and how creating the work has challenged her to represent caregiving in an accurate way while also devising a compelling artistic piece.

Learn more: www.pigiron.org

Mentioned in the show: “The Commercialization of Intimate Life” by sociologist Arlie Hochschild

Music: “Always Late” by Ketsa | CC BY NC ND | Free Music Archive

UPDATE: In September 2019, Nell became the Artistic Director of The Theatre Horizon in Norristown, PA. Theatre Horizon’s Autism Drama Program was featured on The Kelly Clarkson Show. Nell and Director of Community Investment Mydera Taliah Robinson were able to share the history of their Autism Drama Program and its impact on students on National Television. You can watch the segment here.

INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT:

[EXCERPT/INTRO CLIP] NELL – For me that that is the central question as the director of this piece, is how do I both represent the experience of caregiving in a way that the caregivers involved feel good about, and how do I also make it an artistically interesting piece? And I’m actually really excited about that challenge.

JANA PANARITES (HOST) – Hey everyone. I’m Jana Panarites and this is The Agewyz Podcast, where we give you strategies for aging well and wisely. Up next, episode 127.

[MUSIC OUT; SHOW INTRO]

JANA – Since its founding in 1995, the Pig Iron Theater Company has created over 30 original works and toured to festivals and theaters in 14 countries on four continents. Located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, much of the company’s work is eclectic and daring, showcasing material that defies easy categorization. Caregiving is also something that can’t be easily categorized. Layered and demanding, it forces us to engage with ourselves and others in unexpected ways, and calls upon us to play many different roles. Somehow, checking the box that says “caregiver” doesn’t quite cut it.

So to understand the many facets of caregiving, it helps to get creative. Fortunately, the Pig Iron Theater Company is doing just that. Joining us today is theater artist, writer and educator Nell Bang-Jensen. Nell is Associate Artistic Director of the Pig Iron Theater Company, and she’s here to talk about The Caregiver Project, a performance piece in development at Pig Iron. Nell Bang-Jensen, welcome to The Agewyz Podcast.

NELL – Thanks so much, Jana. It’s a pleasure to be here.

JANA – So you’re originally from Burlington, Vermont, which was kinda cool to figure out because I went to the University of Vermont, and you told me that your parents still live there. You told me that you weren’t a primary caregiver for either of your grandparents, but you were a witness to parts of their hospice journeys. What sticks out in your memory of that experience, of being around your grandparents at that time?

NELL – Wow. Yeah. Well, I’ll say, first of all, I wasn’t the direct caregiver for either of them, but you know the loss of my grandfather and then what my grandmother is going through now in hospice care, really opened this world to me of caregiving that I just hadn’t been exposed to yet as a 29-year-old living in Philadelphia. There’s a lot of that work that is a lot of emotional labor, often done by women, although there are others as well, that happens behind closed doors and in isolation. And I think that our society has yet to find very helpful answers for, actually.

So with my, in the case of my grandfather, he and I were very close, I was actually born on his 65th birthday and we made an effort to spend every birthday together after that. We were very close, and with him it was a gradual transition.

He and my grandmother were in an independent living facility that, that did offer more layers of care. But in the end, uh, you know, it was a problem with a valve in his heart and he went into hospice for a few days. We were all able to gather round. And, um, I think I was struck, you know, from someone as a theater artist who’s always observing these human dynamics and interactions to see the way these strangers were caring for him and how amazing they were at their jobs from basic needs to cleaning him to, you know, dealing with human fluids – we don’t like to think about, but how professional they were and you know, performing these intimate acts for strangers.

And then my family being there, you know, watching them and feeling helpless, and also trying to help, and having those last few moments with him, the labor the hospice workers were performing from, you know, managing us as well as family members and him. It just made me think what, what strong and incredible people they were, who really saved my family during that time.

And it ended up being a very peaceful death. I was, I was in the room as he died with I think six other family members. And um, you know, it was a very, his breath just got, there was more and more space between each one until there were no more. And I was holding his hand while he died. And so having that experience, you know, at that point I was in my mid-twenties, really gives you a lot of perspective. And I’m now with um, my grandmother who is my last remaining grandparent, she recently made the choice as she has congestive heart failure and her heart is now so swollen, it’s putting pressure on other organs and causing problems in her lungs and with fluids, and she’s been in and out of the hospital for the past few months, and she recently made the choice to go to hospice if she has a breathing episode again, that she does not want to spend the remainder of her days in the hospital.

So I actually went up and spent New Year’s Eve with her. We snuck a bottle of champagne into the rehab facility, for a picnic. And so it’s going to be, I think, unfortunately not the situation where we’re all gathered around and it could happen at any time. But um, I’ve also been struck by, for her, the difference in their deaths or, or inevitable death, and how she’s managing the emotions of that with saying her goodbyes and also trying to really envision and be honest with yourself about what she wants the last few weeks or months of her life to look like. It’s really inspiring to me.

JANA – Before that, were your grandparents in need of care? And how old was your grandfather when he died? And how old is your grandmother now?

NELL – My grandfather was 91. I know because I was 26, and we were 65 years apart exactly. And my grandmother is 89 right now. And they were living together, they were sort of being each other’s caregivers. I also have an aunt, my mom’s sister, who lived about 10 minutes away from them, so much of that care did and continues to today fall on her shoulders. They live in western Massachusetts, and my parents live in Vermont, so they will also come down and help out. But I think most of the burden ends up being on those who are close by, which is a challenge.

JANA – Yeah, so was that your first real exposure to end-of-life issues? I mean, that was very firsthand.

NELL – Yeah, it was, it really was. And my father’s mother died when I was 12 and she had Alzheimer’s and I, you know, my memories of that are not really that far into the end of her life. She was in Washington DC at that time and we were sort of far away, but I do remember seeing – I actually have this vivid memory of being, you know, 10 or 11 and we visited my grandmother who was in a nursing home at that point.

And with her Alzheimer’s, I remember she pulled me aside, and at that point, you know, I think I felt she, she hadn’t been herself in years, and so I felt – not scared of her, but just sort of uncomfortable because it was so unpredictable – what was gonna happen – which was such a tragedy because she’s just an amazing person.

But at that point she wasn’t very lucid, and she pulled me aside and she said, Nell, you know, there’s something very special about our family. And I said, what? And she said, We’re related to Santa Claus. And she had in her mind about, you know, our Scandinavian heritage and how this all happened. And I remember laughing as a kid, because I was so surprised and I thought it was a joke. And I remember looking across the room and just seeing my dad crying, who had overheard.

And that made such an impact on me as a child, just to see my father not recognizing his mother in this moment. So that did stick with me. But it really was witnessing my grandfather’s death a few years ago that made me think, not only just, you know, about life and time and how we all move on from this world, but also the economy of it in our society of caregivers, and who does that work and who carries those burdens.

JANA – I think it’s a tribute to your family that you were encouraged to participate in the process. When I was in college, my grandfather died and my parents didn’t tell me that he had died until I came home for my winter break. We’re Greek, and so we put a lot on the table, but that was something they wanted to keep from us, you know, and I really regret that because I’m sure that had I had an experience like you had, I might have been less afraid of death. I’ve gotten less afraid of it, but I think what you went through, I have to think it in some way is going to help you down the road.

NELL – Yeah, I think so too. And I think it’s, it’s helped my grandmother also. She’s still actively processing her decision. It’s true. I think people try to shield children from it, or you know, sort of soften the truth and it’s actually, I think the larger question is, what are we hiding? And what a missed opportunity that is, actually, because maybe the reality is less scary than our imaginations.

JANA – Hmm. Moving on, I read that you went to Swarthmore College. You’ve done a lot of acting. You’ve even founded your own theater company. Tell us how you wound up at the Pig Iron Theater company.

NELL – Sure. Yeah. You’ve done your research. So I went to Swarthmore, and while I was there I really fell in love with the Philadelphia theater community. I think it’s an underrated, very experimental and scrappy, scene that we have the advantage of being right near New York, but not New York, so it’s a much more affordable living wage for artists and yet they have access to those resources.

Many, many shows you go to in New York now have actually been developed in Philadelphia, because New York prices are so astronomical. And so there’s a great fringe festival here, and there’s also large regional institutional theaters. So there’s really a mix. And I became attracted to that scene while I was in college. I produced a show in the fringe festival with some friends, and the theater department there was really a fan of collective creation – so this idea that, instead of starting from a script you really start with the people who are in a room, and you start with a situation or an idea or a topic that you want to explore.

And through that, either you all as writers or a playwright working with you, will create something for that specific circumstance for those specific people. So that was great because up to that point I had really only been exposed to high school drama club, which was really, really traditional. I mean I remember getting a call back once for a production of Guys and Dolls.

JANA – Every high school does it, right?

NELL – Every high school does it. And I remember, she would line all the girls up by height in callbacks because she wanted to make sure they weren’t taller than the male leads.

JANA – Oh my gosh.

NELL – And now I look back and think, those were the priorities, really? So that was where I was coming from and then. And then the idea that we could be making our own work about something we were interested in was so exciting to me. And especially the dynamics involved in doing so, just learning to collaborate like that. It’s really hard, especially for college students with huge egos.

And navigating all of that is really important I think. So I fell in love with it, but was sort of hesitant to pursue a life in the arts because I knew how challenging it was. And I ended up doing a research fellowship for a year after college that took me to all parts of the world. Not connected to caregiving or theater really, but I ended up doing sociological research on the stories behind first names, so how people get their names in different countries, and the cultural and religious and political traditions they embody.

I came back, really didn’t know what to do, you know, classic, kind of 22, 23-year-old thing of what am I going to do with my life. And I had had a director from Philadelphia in college, who invited me to come act in the show she was making, and I’ve been here since. So that was about six years ago. So I started freelancing. I was nannying part-time, which is also a different form of care. I was teaching theater to kids. I was acting. I also do dramaturgy, which is sort of the research behind the production and also connected to new play development.

So I’d work with playwrights who were trying to write a script but hadn’t done it before about structure and dialogue, which I love doing. And I was also making my own work on the side. I then was hired in the artistic department of the Wilma Theater, which is a big regional theater here, and realized I loved making the work.

I loved being in a rehearsal room, but I also really liked being part of an organization who is asking these questions about what shows should we be doing, and what’s our mission and what role do we serve in this community, and how do we diversify our audiences and who is this work actually for? And so I applied for a grant in artistic leadership because I realized I really liked the sort of big picture thinking behind those questions, and received it.

And so for the past 18 months through the grant, I’ve been in residence at Pig Iron as their associate artistic director, and with that have been doing a lot of work learning from models of theaters around the country who are making work with their communities, which is something I’m trying to do in The Caregiver’s Project.

So I think theaters are sort of at a precipice right now where, you know, some people really see it as a dying art form because it’s much easier to turn on Netflix and then show up at a certain time or place, especially in January, when none of us want to go outside. But it’s really a question of how are we engaging another generation and not only that but more diverse communities than mainstream theaters have usually been sort of aiming their work at.

And I think it’s really not enough to just do Shakespeare and say, okay, now you need to come see it. But I think if theaters want to make work that’s for the whole city, I think they have to be making work with people beyond their bubbles. So I think they need to actually be inviting them into the rehearsal process.

JANA – And I should think that these newer models are more attractive to folks in your generation particular because a, they can’t afford to go to Broadway shows, likely. And b, they really want to sort of carve their own path in terms of creating a theater of that kind and also drawing audiences in, and finding new ways of talking about real life issues.

NELL – Yeah, exactly. I think, you know theater has its roots in democracy, and then somewhere along the way it became sort of elitist at least in this country in terms of you know, the average ticket goer. And I think there’s a way of sort of bringing it back to the people, and there’s some really interesting models of theaters who are doing that. And I think the way to do that is not just to say, okay, we made a play, come see it, but to look around and say what are our people in our community talking about?

What are their home lives like? How could this be a process that actually serves them? Every nonprofit I think be thinking about that, including arts organizations and maybe doing a big show on a main stage is actually not the best way of serving a particular community. It might be also engaging these people in the artistic process, and using tools and skills we have as theater makers to give people an experience that goes beyond just sitting in a seat and watching a show.

JANA – Right. It kind of gives a whole new meaning to the term support group.

NELL – Yeah. Exactly. Exactly.

JANA – Well, that brings us to The Caregiver Project. Let’s talk about that, and what inspired the project. Tell us what it’s about.

NELL – Sure. Well, one thing I’m trying to do, in thinking about these models for making work with the community you’re a part of is actually just paying attention to my surroundings, and thinking less about what I as an artist want to explore and more about, okay, what are the people around me interested in? And just walking around the neighborhood around Pig Iron, I was noticing all of these social service organizations. There was a visiting nurse group, there’s a children’s crisis treatment center.

There’s a Lutheran settlement house that runs a caregiver support group. And I had been thinking about this question of care, I think in particular in relationship to gender, you know, which has been a topic on everyone’s mind this year and years before as it should be, and you know, thinking about who does that work.

And because of my own experience with my grandparents, and then also giving care in another way as a babysitter and nanny in my early twenties, you know, this question of these intimate acts often done between strangers or for people caring for family members, how it can completely transform their life and the emotions associated with that became really pressing.

And I thought, okay, that could be a topic that to me is actually really interesting dramatically. It brings up this larger question for me about what do we owe each other? Which is just a huge question, but also seemed like something that people in the neighborhood were directly impacted by and would want to talk about. So I started making these partnerships with people in our community in June. Going to organizations first, and then actually you know, knocking on doors and trying to find individuals to meet with people who want to be involved.

And I’ve been holding these, what I call story circles, which are sort of a support group. People come and I make sure to provide snacks because that’s always a good way to get people to a place, and they tell stories about their caregiving experience. And this is people who are community members, and then also people on the creative team, so the set designer the composer, many of whom have their own caregiving experiences.

So it’s been really interesting to have everyone participate in the process in that way. And then together based on these stories and materials, we’re going to be generating a play together. And I don’t yet know what it will look like, if it will be, you know, one narrative about one caregiver or whether it will end up being a lot of scenes and skits about it. There is a composer working on the piece, so I know it will have music in some way. And it will just go up for two days in June, it’s going to be free and open to everyone in the neighborhood. And I’m really excited to sort of view this as an experiment of generating material with the people in our neighborhood who aren’t theater artists.

JANA – Right. So when you were going around and talking to people, knocking on doors and what have you, how did people initially react to you and the whole idea of this?

NELL – Yeah. I mean it ran the gamut. Some of it was like political canvasing, where you get doors slammed in your face, people who don’t want to talk. Also the neighborhood that the theater is in is largely Hispanic, so I had a woman come with me, a partner [inaudible] who’s a Spanish speaker. Um, so it was very helpful to have her there. But actually what I’ve been surprised by is the caregiving connections in places I wouldn’t expect it. So sometimes doors were slammed in my face and sometimes it was the opposite.

I remember walking into a pizza shop that’s a block away from Pig Iron Theater where the staff goes all the time for lunch, and I asked the woman behind the counter, I said, you know, can I leave these fliers here for the show? And I explained it to her and she said, yeah, you can leave the flyers here, but I also want one. I want to come. And here it was this woman making the pizza behind the counter. She’s also a caregiver for her mother at home right now.

And it’s something so many people carry, but that’s not always visible. So that’s been really exciting to me, is to see how many people are actually looking for an outlet to talk about it. And I think it’s also, you know, you said this great thing in your introduction about how there’s not an easy categorization of a caregiver. And I think even that label is one that might be new to some people. They’re just, naturally, are caring for an aging or ill family member. And I think actually identifying as a caregiver and thinking about what that is in their life can be a powerful label.

JANA – Yeah. I think it cuts both ways. I think because of how we have, we’ve painted it with such a broad brush that for some people I think the label is offensive. And for others I think it’s ennobling. I’m not sure. I think it cuts both ways. So when you’re going – you went out and you brought people in for what sounds like the story circles, that sound like rehearsals for a final show. Right? So are you going to pick people from the various story circles that you’ve already had or–

NELL – Yeah, exactly. And people are welcome at the story circle even if they don’t want to be in the play, if that’s not their thing, which I make very clear. You know, if they just want to show up for one afternoon and that’s it, then that’s great. Because some people might be interested in saying – you know, one person said, you know, I don’t want to do the play but I have this really powerful story about my mom as she was dying. And she’ll share the story and say, you know, you can use that in the play if you want, even though she doesn’t want to be involved herself. And then there might be – you know, I have one person who’s there who the paid caregiver and you know, rightly so, feels sensitive to questions of confidentiality with her clients. And so she doesn’t want to share much about her experiences there, but she really loves to sing and she wants to do that in the show.

So I have some people who really want to be part of generating material, and some people who are really excited about the performance element. But I’m doing a few more story circles, and then there’s a week in March where we’re really starting to sort of hone in on, okay, what stories do we want to tell? What’s the structure of this piece? What does it look like? And then we will have rehearsals every Saturday for the month of April and May. And then the performance will be in June.

JANA – I see. So the story circles right now are sort of a way of gathering material and you’re taking notes and maybe getting some cast members. So to what extent are the actual company members of Pig Iron going to be involved, if at all?

NELL – Yeah. I have two professional actors in it who are, you know, acting and also helping to generate material because Pig Iron is really – we actually have a graduate program in devised performance, and devised performance is the kind of performance I was talking about where you’re starting with the people in the room rather than the script. So these performers are really good at coming up with material in improvisations or movement, or thinking about another way to look at something. So I’m really excited they’ll be in the room to also help these people with less experience feel comfortable, and you know, give ideas in scenes and things like that to sort of help them go along with it.

JANA – Well I have a kind of an existential question here for you.

NELL – Oh boy.

JANA – I read in the interviews where I first learned about the work that you’re doing. You accurately described caregiving as quote, often quite mundane, menial, quiet and slow. So my question is, first of all, how do you dramatize something that is, at least on the outside inherently undramatic when you know there’s so much emotional drama? I should imagine that this is quite a challenge – to dramatize something that at least outwardly is not dramatic, because it’s also done in isolation, so we don’t really see that drama, if that makes sense.

NELL – Yes. Yes, it absolutely does and I think for me that that is the central question as the director of this piece, is how do I both represent the experience of caregiving in a way that the caregivers involved feel good about? And how do I also make it an artistically interesting piece? And I’m actually really excited about that challenge and have had a lot of ideas to it already. I actually put that question onto the caregivers at a story circle a couple of weeks ago, and I said, well, in a different way.

I said, you know, what would you want people to see in a play about caregiving? And almost all of them responded, You know, I want people to understand how hard it is, you know. And someone said, I really want them to see the hard, brutal reality.

And you know, it’s interesting because on the one hand I completely respect that, and I also hope audience members leave with a deeper understanding of how much this impacts people’s lives. And at the same time, I know as a theater artist that sometimes actually portraying exactly that is not the most effective way to cause a response.

JANA – What do you mean by that?

NELL – Well, so I think, well, I’m wondering for this piece, for example, I think if it’s one person after another going up to a microphone and saying, and here’s my depressing, horrible story, people tune out and people start to think, oh, I know what this is, I know what this is gonna be. And so I’m actually really interested in how humor can play a role, if there’s a sort of a fiction in it. You know, there’s this woman, Evelyn, I met at a caregiver support group. She’s 74 years old and she’s been caring for her husband who had Parkinson’s for 31 years, and she has given up a lot of things in her life. She was a nurse and she left that to care for him at home.

She used to love glass blowing, was her favorite hobby. And she’s given that up. There’s all these things she’s given up. And she got married I think when she was 19, and even before his diagnosis they did not have a happy marriage. And she’s pretty upfront about that. And it’s really hard because I watch Evelyn, and how it even physically feels like is weighing her down and I, I keep thinking, you know, it’s in many ways going to be such a relief when her husband dies. And that’s not something I am comfortable saying to her, or that I, you know, I’m sure she’s thought it, but she can’t – she doesn’t really even voice it aloud.

And you know, I was thinking about a version, I was like, what if part of this play actually gets to be some kind of fantasy or fiction for Evelyn – that rather than represent her day-to-day is the first part of the show Evelyn on a cruise ship? You know what I mean? It’s how can I actually give the caregivers the gift of play that they’re not experiencing in their daily lives. You know, having something like that, showing Evelyn on a cruise ship and then getting at all of the reasons why she’s not there, you know, the fantasy compared to the reality, might be a more effective way in for people. Because I worry if we just start with hard reality, depressing story, audience members actually stop feeling that.

JANA – Yeah. Well, part two of my existential question is, how do you think the outwardly mundane nature of caregiving and the sort of behind-the-scenes nature of the work undermines our ideas about the value of the work, especially in terms of how we address this challenge? Just a small question.

NELL – Yeah, just a small question (laughter). I’ll tackle it in two parts. One is, I tend to really like work. And this is just kind of my personal artistic take, but I really like work where the ordinary is made extraordinary. So I’m actually really excited about… one caregiver told a story about his father as he was dying, would refuse to use a cane even though he really needed one. And so they would put it in his hand, and his father would walk across the room but wouldn’t put the cane on the ground. He would carry the cane.

JANA – That’s great.

NELL – And you know, from a theater perspective – for me that’s such a beautiful image. That feels like such an image of defiance and dignity, and this man trying to carry his pride with him. You know, he’ll take the cane but he’s not going to use it. And so I instantly see like, 10 people walking around with canes like that, and making it some kind of cane ballet.

So I actually think there’s a way that the ordinary task of sorting out pills or cooking, or putting sheets on a bed – if we see them at a different scale, or we see them set to music, there’s a way in which they can become almost a dance. So I imagine there will be some of that in this piece, is just, you know, actually playing into that idea that it’s repeated, slow tasks… by just seeing them over and over again until they form their own rhythm.

JANA – Hmm… I’m seeing this as an opera already.

NELL – Yeah. There you go. That’s right. That’ll be the next step, once we get to Broadway.

JANA – Once you start scaling it up.

NELL – Right, right. Oh, and then as to your question about the value of the work and how it relates, my thinking has also really been informed by this book by Arlie Hochschild. I don’t know if you know her. She’s a sociologist, and she recently wrote a lot about red states in our midst, so she’s gotten a lot of attention for that. She’s a really interesting woman.

JANA – About what?

NELL – She went and spent two years in some red states, trying to talk to voters leading up to the election. And she has this other book she wrote decades ago called, The Commercialization of Intimate Life that has been really inspiring to me for this project, because she talks about how a lot of the most underpaid tasks in our society are tasks that people just used to assume women would do. So childcare, caring for the elderly. And how when women entered the workplace, those jobs were outsourced often but still not paid very well.

And she even talks about how it affects a global economy. So for example, she used as a case study, a woman from the Philippines who is a nanny on the upper west side in New York, and then she’s sending money home to pay for a woman in the Philippines to watch her own children who are still there. And so the scales that we’re operating on are so fascinating and, you know, it’s sort of appalling to me, too, that often these tasks that are so underpaid are things that were just assumed to be women’s work, and then gradually became jobs but are still not something, usually not with a salary that people can even live on.

JANA – Right. That makes me think about the male caregivers who you might be involving in this project, and if you have any. How do they factor in?

NELL – Yeah. I do. Yeah, I have – one guy in particular, who I just liked him so much I already offered him a role in it, and he signed on for the whole thing. His name is Ivan. And we met because he works at the children’s crisis treatment center, which is right in Pig Iron’s neighborhood. And I was talking to caregivers there about the show. And he also cared for his dad at home as his dad was dying, so he had sort of this dual professional and personal life that revolved around caregiving in different ways. And then he was at the story circle and talking to me about the work he did, and it turned out that he immigrated here from Peru 15 years ago, but when he lived in Peru he went to theater school there and he was a trained actor performing in Peru. But since coming to the United States he hasn’t had the opportunity to perform.

JANA – Now’s his chance.

NELL – So I’m very excited that he’s involved.

JANA – That’s really great. I suppose you could really – I’m probably stating the obvious – but you can really create a very diverse group there. You probably want somebody who’s from your age group as well, right? Because millennials make up a quarter of the caregivers in the United States.

NELL – Yeah. Yeah. At my very first story circle when I was just getting started, there were five people there, which at first I was disappointed by. Then the rest of the theater company reminded me, they were like, No, you have five caregivers who want to be in a play? That’s actually a huge number.

JANA – Yeah, that’s huge.

NELL – And it was really interesting because they just spanned the gamut in terms of age, in terms of race, in terms of their experience. I mean I do the terminology around caregiving, I feel like needs to be so much more specific, and I’m as an outsider to it am just learning the terms. But it ranged from one woman, who I think was younger than me, who had been volunteering her time to care for an elderly woman just a couple of days a week, I think through a church group. She just went there maybe two hours, three days a week. So that was her experience.

And then I had people there who were living, breathing it every day, often with a family member. At first I wondered, okay, do I need to narrow in on a certain population, a certain definition of caregiver, especially this difference between paid caregivers as opposed to informal, unpaid, often family members or friends.

But I was talking to this social worker who runs a support group for caregivers, and she told me she actually really loved that there would be paid home health aides interacting with people caring for family members, because in her work she had often seen a rift between them. Just because I think for some family members they feel like a paid aid will never take care of their family member in the way that they would, and I think that’s a really hard thing. So she was excited about the idea that these different populations would be collaborating on a piece together.

JANA – Yeah, I think that’s probably true, but at the same time I’m sure that anyone, including me, who has hired and has paid caregivers, there’s a real connection there for a lot of families with the paid caregivers and their carrees. And there are so many permutations to explore with paid caregivers, including sexual harassment.

NELL – Yeah.

JANA – So you really open up a huge can of worms, you have to make choices there. But it’s great that you’re including some paid caregivers because certainly they’re going to be called upon as the years go by and as our population ages, and fewer caregivers in families are going to be available, they’re going to be essential in caring for people. So how circle story circle sessions have you had so far?

NELL – I’ve had two so far.

JANA – Okay. And I was going to ask what you want the audience to take away from this theater piece? You sort of touched on it earlier, but I wondered if you could add to that, what else – what do you want the audience to take away from this?

NELL – Hmm. I would love for them to think more deeply about where our responsibilities as humans lie to each other. And I think that’s a huge question that’s political and social and cultural, but also things that people are grappling with. You know, I see these family members, for example, running – okay, can I slip out for 15 minutes to go do this errand? Is it worth the risk that I’m taking to leave this person alone? And I think, you know, those are micro, minute decisions they have to make on a daily basis, but it ties into this larger question of, you know, what are we sacrificing for each other?

And what’s appropriate to? And when is it too much, and when is it not enough? So I would love for them to be thinking about those big picture questions. And then also, I do hope that there is some kind of sociopolitical takeaway that we really need better systems for this in this country.

JANA – I hope you invite some public officials.

NELL – Yes, I’m planning to.

JANA – Good.

NELL – I’m planning to.

JANA – Okay. So how can people learn more about the project, and maybe even get involved in some way?

NELL – Well, they can go to the Pig Iron website, which is pigiron.org. It’s not up there yet, but it will be in a couple days. And they can also just email me. My email is just nell@pigironpIgIron.org.

JANA – Super. Now I want to give you the opportunity to add any last thoughts. Is there anything else you’d like to talk about?

NELL – Well, I would be curious from you, if you don’t feel too put on the spot, but I just think it’s an interesting question to be asking people who have had more caregiving experience than I have, and you’ve studied it in such an intense way through all of your conversations with people. But what would you want to see in a play about caregiving?

JANA – I’d like to see caregiving celebrated. I’d like to see the actions of caregivers celebrated. I’d like to see their work celebrated. And I think that in order to do that you have to show how difficult and wrenching it is, and how people come out on the other side. So I would like to see the full spectrum of emotions on display. Caregiving is messy, but life is messy. One of the things we didn’t talk about that maybe you could we could touch on. First of all, do you have siblings?

NELL – I do. I have an older sister.

JANA – Okay. So has this experience of working on the show sort of opened up your eyes to your own caregiving needs down the road? And does it make you think about how you are going to be cared for down the road?

NELL – It has made me think about it a lot, you know, maybe almost kind of neurotically for a 29-year-old… who hopefully has many years ahead of her, although we never know. But I have been thinking about it so much. I think between these experiences with my grandparents – my sister also had a baby last year, and so it’s the first of the next generation in the family. And so that brought up a lot of questions with care. And she and her husband had to decide, okay, if something happens to us who has custody of this child?

You know, all of those questions that we don’t really want to think about but should, I think. And my parents recently, you know, updated their will as they were going through this stuff with my grandmother, to the point where we were all just sort of joking about it because it is sort of like you open Pandora’s box and it all comes tumbling out about the things that you need to be honest about with each other.

And you know, my grandmother was even that way, before she had even made the decision to go to hospice. When I would be over in her apartment she would say, Okay, I want you to pick out a piece of art because, you know, your cousin is getting this one and your aunt is getting this one. And she, you know, always had this attitude about it that, you know, knowing one day was going to be the end. And so I think, yeah, right now my family and I are in this period of transparency about looking at this straight in the face.

JANA – I think it’s great that you’re having the conversations.

NELL – Yeah, yeah. I do, too.

JANA – A lot of people don’t talk about it. We didn’t talk about it, in my family. But I’m really happy for you, even if it’s somewhat macabre, that you’re talk – that you talk about it with your parents because I think that’s really healthy.

NELL – Me too.

JANA – And I love talking with people like you who are really approaching this in creative ways, because I think that’s how you’re going to get people to pay attention.

NELL – I hope so. Yeah, I know, you can only give – I mean it’s kind of like climate change, it’s like you can only give people so many articles, right?

JANA – Right.

NELL – Then there’s a point where we just need new ways of reaching them, because this isn’t working.

JANA – Amen. And that is a great note to end on. We’ve been speaking with the Pig Iron Theater Company’s Associate Artistic Director, Nell Bang-Jensen about a new work called The Caregiver Project, a performance piece in development at Pig Iron. And we’ll have all kinds of links on the Agewyz website to how you can connect with Nell and learn more about the project if you missed what she said earlier in the show. Nell, thanks so much for being on the show. It was really great talking with you.

NELL – Thanks so much for having me. And thanks for all the work you’re doing. You’re also a storyteller, clearly, and I’ve been loving listening to the podcast.

JANA – Thank you. And good luck with the show. I’m going to be keeping tabs on it.

NELL – Thanks.

JANA – Bye-bye.

NELL – Bye.

UPDATE: In June of 2018, “The Caregivers” went live at Philadelphia’s Pig Iron Theater Company. The social practice performance piece sold out all shows.

Scattered: My Year As An Accidental Caregiver is available in paperback and eBook at

Scattered: My Year As An Accidental Caregiver is available in paperback and eBook at