Cynthia Lim thought she had the perfect life: a loving husband who was also a successful lawyer, her own fulfilling career, two sons thriving in high school and a home in LA loaded with books, music and art. It all fell apart in June of 2003 when her husband, Perry, suffered a cardiac arrest and brain injury, lingering in a coma for ten days. When Perry woke up, he was unable to form sentences and he was completely dependent on others. Cynthia talks about the wrenching realities of her new life after Perry’s catastrophic event, from wanting to leave him in an institution and battling with the medical community to finding services and support for Perry all on her own and caring for him throughout his recovery. She did it all while working full-time, seeing one son off to college and guiding the other through high school, and trying desperately to find connection with her husband of twenty years. Cynthia’s story of reinvention and reimagining life with disability is captured in her memoir, “Wherever You Are: A Memoir of Love, Marriage, and Brain Injury.” This episode is sponsored by Hero.

Subscribe to The Agewyz Podcast: iTunes

Got a story to share? Email us any time at jana@agewyz.com

Link to Cynthia’s book: “Wherever You Are”

Link to Cynthia’s website: cynthialimwriting.com

Connect: Facebook | Twitter

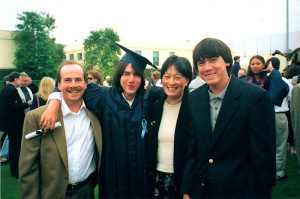

Perry, Zack, Cynthia and Paul on the day Zack graduated from high school. Soon after this photo was taken, Perry had his heart attack.

INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT:

JANA PANARITES (HOST) – Cynthia Lim thought she had the perfect life. A loving husband who was also a successful lawyer, her own fulfilling career in education, two sons thriving in high school, and a home in Los Angeles filled with books, music and art. It all changed in June of 2003 when Cynthia’s husband of 20 years suffered a cardiac arrest, which then led to what’s called anoxic brain injury. After the injury, Cynthia wrote about her experience of caring for her husband, Perry, and herself in a memoir titled, “Wherever You Are: A Memoir of Love, Marriage and Brain Injury.” It’s a story of reinvention and reimagining life with disability. Cynthia Lim recently retired as the Executive Director for Data and Accountability for the Los Angeles Unified School District. She’s been featured on KRCB’S “A Novel Idea,” on the NPR podcast, and her essays have appeared in Hope magazine, Kaleidoscope and Witness magazine, among other publications. Cynthia joins us today from Los Angeles, where she’s lived with her family for the past 30 years. Cynthia, welcome to The Agewyz Podcast.

CYNTHIA LIM – Thank you so much for having me.

JANA – Well, I’d love to put this in context for our listeners. I know, you grew up in Salinas, California and your husband, Perry grew up in Torrance, which was worlds away – culturally, I should say, maybe not really physically. And I really appreciated that sort of differentiation in the book. Can you tell us how you met and a little bit about your upbringing and your environment versus his?

CYNTHIA – Yes. So we met at UC Santa Barbara, on the first day of college, actually. We were standing in line to register our bikes. And we, you know, fell into a conversation. So I grew up in this very traditional Chinese family in Salinas. My parents were grocers. So I had a very, kind of sheltered upbringing, you know, didn’t really know much about big city life or arts and culture and that sort thing, especially Western culture, because my parents were immigrants, and we spoke Chinese in my house.

CYNTHIA – And Perry was, you know, from the LA area, he’s from a suburb of Los Angeles. But to me, he seemed really worldly. I mean, he had done all these things and taken advantage of living in the big city and was culturally aware and he was just so different. And his background, he came from a Jewish family that wasn’t very observant, but, you know, in Salinas I had never met anyone Jewish. So it was kind of this meeting of two very different cultures. And that’s what made him, I think, so interesting and appealing to me. It’s like, here’s somebody that was so different from the world I grew up in.

JANA – And you really drew that picture, so clearly. I really had that sense, in the book. You really captured that so well. So you had this perfect life. Beyond what I described in the intro, what did that look like for you? Paint the picture for us.

CYNTHIA – Well, you know, we were struggling college students together. And after, undergraduate school, we joined VISTA. We were VISTA volunteers in the Midwest and living on poverty wages. You know, VISTA’s like the Peace Corps, but internal – in the United States. So we really had, like, nothing. And, you know, we got student loans to get through graduate school, and we get out of graduate school, we land these jobs, it’s – you know, finally paying the salaries after all these years. So, you know, maybe to others, it wouldn’t seem like – we didn’t have that much, but to us it was like, Wow! You know, both of us earning full salaries, we thought, Wow, this is a really luxurious lifestyle.

JANA – Two salaries – woo hoo!

CYNTHIA – Right. As opposed to, you know, student wages or VISTA volunteer wages. And you know, from there, we bought a house, we had two sons, and Perry had this philosophy of, you know, working really hard and playing really hard. So he made partner early in his law firm. And he worked very hard as a, he was a corporate bankruptcy attorney. But he also would really relish, like, the time that we had together as a family.

CYNTHIA – And so any time the kids were on spring break, or in the summer, he would plan these vacations so that we would always go backpacking in the mountains, in the Sierra Nevada, here in California, or he would plan, you know, some exotic vacation somewhere. So he really relished the time together, that we had as a family because I think he felt like, you know, the kids are only going to be young once. And we need to set aside the time and spend with them. And so our sons were teenagers at the time of his heart attack. They were 15 and 18. Our oldest son had just graduated high school, and was going to go off to college in the Fall, when he had his heart attack. So… that changed everything.

JANA – And that was a very dramatic scene, that the book begins with and the reader – as a reader, I was just drawn right in from the very beginning. So the book opens up with a dramatic scene that takes place in a Portland hotel room. You and your husband had gone on a weekend in June. Cynthia, I know this is probably hard for you to talk about. But can you tell us what memories you have of that event?

CYNTHIA – It was just a blur. You know, it’s one of those things where you think, what’s the worst thing that can happen? And then it happens. And everything, you know, everything that people tell you like CPR, or, you know, what to do in an emergency? It’s like, my mind just went blank. It’s like I could not remember any of those things. It’s this sense of panic that I hope that no one will ever have to experience because you’re just like, paralyzed. You’re just like, Oh, my God, what do I do? What do I do? And you know that there’s something you should be doing, but you can’t – I couldn’t conjure it up. Like, what is it I’m supposed to be doing? What were all those lessons that we took, and you know, it was just sheer panic.

JANA – And you had to absorb a lot of information really fast. Your doctor said that Perry needed a stent, or he’ll die and you had to consider the risks of surgery, and then the boys are arriving. Wow, I believe that it’s a blur. Because I know that when my father died – he died suddenly – and that period is a blur for me. So whatever else you remember from the event before he came home, I wonder if you could share some of that with us?

CYNTHIA – Yeah, well, you know, I kept – I am a journal keeper. You know, I’ve been keeping a journal since high school. And it was a way of calming myself to just write, in the midst of all this. So I just remember being in the emergency room in the hospital, in Portland, not knowing what was going on. Our kids were on a plane, you know, headed to Portland. I didn’t know if he was alive or, you know, what the deal was. We just, we arrived at the hospital, they whisked him away and they put me in this room. And so I just jotted things there. Like, I don’t even know what’s happening. You know, my feet were cold. Those kinds of things.

CYNTHIA – And throughout his whole time in the hospital – he was in Portland for two weeks in a coma, then we were able to transport him back to Los Angeles. He was still in a coma for probably a few days. And then he woke. And he was in the hospital for like, another month. And he went to a rehab hospital. And then he went to this residential facility. So throughout that time, all this new information is just being thrown at you. I’m interacting with all these doctors and therapists and nurses and not really knowing, you know, what’s what. So writing was my way of just organizing my thoughts. And so a lot of the book about those parts were really drawn from what I had written and remembered in my journal, because I knew five, six years later, I would not be able to remember all those details.

JANA – Well, spousal caregiving is so unique to begin with, let alone after a traumatic event like this. I know that it was not the retirement that you envisioned. One day, you know, you’re on an equal playing with your partner, and then it’s completely upside down. I wonder if you could talk a little bit about what it was like for you, being a caregiver for Perry and how it evolved. And if you want to refer to any examples from what you remember, feel free to.

CYNTHIA – Yeah. You know, I think initially, it was really frightening, I think when you’re a caregiver of someone with a brain injury. Because at the period when he first woke through his coma, you know, I’m expecting that he’s going to be the same person and the same voice and have the same memories. And what would happen in his brain is – with anoxic brain injury, it’s like it’s diffused throughout your brain, it’s not one part of your brain that’s damaged, and then other parts, you know, compensate for it. So in his case, it’s like every part of his brain was a little bit damaged.

CYNTHIA – And so his speech at first came back in whispers, so he wasn’t speaking into his normal voice. And then he didn’t initiate speech. So if you were sitting together, he wouldn’t say, you know, how are you doing today? Or, you know, what’s happening? He was very passive. So he would understand everything that was said to him, but he wouldn’t initiate speech.

CYNTHIA – And initially, when he woke up from his coma, he went through this agitation phase. I think every brain injury patient goes through that, where their mind’s just kind of a jumble. And they’re trying to make sense of things. And so that part was the most frightening because he was this person they didn’t recognize. And when he was in the rehabilitation hospital, that’s where it was the worst. So he would walk into other patients’ rooms and, you know, say he was searching for a phone or something, just not making sense. And I would have to be there and the nurses would be there. We tried to get him back in his room.

CYNTHIA – It’s just really frightening because physically, he’s still looked like my husband, but mentally, it was like, I don’t know who this person is. And I don’t know how I would deal with this. And then he went through this phase where he was taken off his clothes, and I was thinking, Oh, my God, what, what am I gonna do when I take him home and he does that? I won’t be able to go out in public anywhere with him. So it was a very, very frightening experience. And I imagine it’s probably what a lot of spouses go through if your spouse has dementia or Alzheimer’s, you know, where their mind is just not making sense.

JANA – I thought it was interesting that you wrote, “He wasn’t aware of his deficits. He thought he could manage, but he couldn’t.”

CYNTHIA – Yeah. And in a way, it was almost a blessing that he wasn’t aware of his deficits, because I think if he was aware, maybe he would have felt the same sense of sorrow and sadness that we did. But yeah, he – there’s even a term for it in the, in the disability literature. They call it “anosognosia” or something where, you know, if you asked him, he would say, Oh, yeah, I can walk from here to, you know, to the pier, or I can hike this trail. And then and, you know, physically he can’t. But it didn’t seem to bother him that he couldn’t.

JANA – You had this period of constantly feeding hospital parking lot meters, being at the hospital. And your, your son, Zach eventually said, Mom, you need to go back to work. I wonder if you could talk about the isolation you felt and being cut off and then going back to work?

CYNTHIA – Yeah, it’s such a, it is such an isolating experience. You know, that first month or so afterwards, where your entire life is being in the hospital, sitting next to his bed, monitoring every nurse, every medical interaction, and that becomes your world. And it was just a strange existence, where the only people you’re interacting with, it has to do with illness and disability and medical doctors. And I wasn’t even aware of the effect that it had on me. But, you know, I was looking really horrible, then. I wasn’t eating properly, I wasn’t exercising.

CYNTHIA – And stepping back into work, the hardest part was, you know, facing everybody that wants to talk to you and ask and, you know, you have to tell and retell the story. But once I got into the work, I found it’s so comforting, because it was this affirmation that I had another life other than disability, and other than my spouse’s disability – that I wasn’t the one that was brain injured, and I still had a life. So I think that was the very first step in acknowledging that, as a caregiver, you have to like pay attention to your own life. You can’t just immerse yourself in your spouse and that illness.

JANA – Yeah, you learned a lot about what to say and what not to say to someone going through a catastrophic experience. I thought you did a great job of highlighting some of the crazy questions and comments that you had to field. People often want to say the right thing, but they don’t really have the language for it.

CYNTHIA – Yeah. And I think that, you know, people really do care and they don’t know what to say. But there are some things that are, like, you should not say.

JANA – Such as?

CYNTHIA – Well, I, you know, I, I used to hate it when people would say, Well, you know, God doesn’t give you more than you can handle. I would think. that is like the stupidest thing to say. What are you saying? That somehow I deserve to get more than somebody else? I mean, you know, I don’t know. It’s just, it’s just such a bizarre thing to say to someone.

JANA – I guess that’s a coping mechanism for the person who says that, too, because they just don’t know what else to say. I don’t know. I won’t get too deep into that, but

CYNTHIA – Yeah. [both laugh]

JANA – So your son thought about – your son Zach thought about delaying college, while Perry was still being hospitalized, I think, or even maybe at this point he was at Casa Colina.

CYNTHIA – Yeah.

JANA – But you said, No. Why was it so important to you that he get on with his life?

CYNTHIA – Well, so my, my father passed away when I was seven. He was killed in a plane crash. And my mother was left with five kids and a business. And you know, she was an immigrant, she didn’t speak English. And from that point on, she totally depended on her children to help her through life, basically. You know, we had to translate for her. And we felt this tremendous responsibility for her throughout our adult lives, you know, because she was this helpless widow. And I didn’t want my sons to go through that. I wanted them to live their lives without guilt, and not feel like they had to stay at home, take care of me, or that I was dependent on them. I just remember what it felt like for me to go away to college – that sense of freedom that I felt, being a freshman in college and being with this whole cohort of kids starting school at the same time, and I really wanted him to have that same experience.

JANA – Mm-hmm. And then you went to orientation with Zach, without Perry.

CYNTHIA – Yeah. All those things, I think all those things that you used to do as a couple, but then you have to do alone? They were so hard, you know, because you depend on your spouse so much to share your thoughts, and especially something like that, so emotional, as you know, your first kid going to college. It’s just such an emotional thing.

JANA – Yeah. So Zach went to NYU. And you came back and you were working full time and visiting Perry at rehab. How did you manage that?

CYNTHIA – You know, I look back now and I think, How DID I manage that? I don’t know. I think you know, when you’re in the midst of it, you just put your head down and you do it. And you don’t even think. I don’t think I had much else in my life other than going to work, visiting Perry, and then making sure that Paul, my younger son, was taken care of at home too. So, it was so much that I just, I don’t even think I could think about it. I just did it, you know?

JANA – Mm-hmm. I really appreciated the passage where you had that sobering conversation with the intake person, Lisa, explaining, This is how insurance works. I mean, that was really, really helpful. Maybe you can talk about that a little bit – the shock of that conversation.

CYNTHIA – Yeah. Unless you need to use it nobody really tells you, this is how insurance works. And so I was so bent on just bringing him home, you know, because I was so convinced that the best place for my husband was at home, where we could take care of him. And this intake counselor was trying to convince me to send him to a residential treatment facility. Because most health insurance companies, they have a benefit that they call – it’s like a nursing home facility benefit, where they pay- well, mine paid up to 100 days. And she said if you don’t use it, it just goes away. And you can only use it if you’re moving a patient from a rehab facility to a nursing home. If I brought him home and then decided, like, Oh, I can’t handle it, he has to go to a nursing home, I wouldn’t be able to place him there because he had to come from an acute medical facility to a nursing home, which – I’m like, how many people know that?

JANA – I wouldn’t have known that. Is that standard, with all insurance plans?

CYNTHIA – I think so.

JANA – I think it is.

CYNTHIA – So it was like this mystery to me. Like, my experience with the medical community up to this was, you know, having babies in the hospital, which is like a really happy thing. So you’re faced with these neurologists, and these therapists and some of them are just really dour and pessimistic. And they don’t give you any sense of hope.

JANA – Yeah, you gave up on the medical community after a certain point. You know, you stepped away from Western medicine. Tell us how that worked out.

CYNTHIA – Well, you know, it was so limited. And I think especially for brain injuries, the common thought in the medical community is that after a year, there’s no more improvement. And in Perry’s case, I think they paid for maybe like three or four months after he came home. So that was within a year of his brain injury. And one of his speech therapists wrote something in his notes, like he thought Perry had plateaued. And that was enough to trigger up and down the chain, like – Oh, there’s no more improvement in this case, further therapy isn’t going to do any good.

CYNTHIA – And so they just cut off physical speech, occupational therapy. And I was incredulous. I was like, How could you do that? Like, what am I supposed to do now? It wasn’t even a year after his brain injury, and I’m just – I’m getting used to having a caregiver in my house while I’m gone. How we supposed to fill up his days? Like, what do families do? And they weren’t very helpful at all.

JANA – And what did you do?

CYNTHIA – In my spare time, I searched the internet for anything about caregiving in Los Angeles, classes for brain injury. I heard about something from the Stroke Association. Even though he didn’t have a stroke, a lot of his symptoms were like post-stroke. And so I just had to become like this advocate, searching the Los Angeles area for any kinds of classes.

CYNTHIA – So I contacted hospitals, I contacted, like I said, the Stroke Association, and I found this wonderful, wonderful class at our local community college, for acquired brain injury. And that was a lifesaver, because they had exercise classes, they had speech classes and computer classes for people like Perry that were brain injured. And so that was a total, total find.

JANA – Yeah, I really appreciated the passage where you talked about getting used to having lots of people in your house, and your house wasn’t your own. My mom lives with my sister and my sister works full-time, so we have a team of caregivers, and my sister feels like her home has become a hotel.

CYNTHIA – Yeah. You know, I think caregivers have to get used to that. Just the fact that there’s like another person in your life. And it, it’s like a very intimate person that’s, you know, helping your loved one with bathing.

JANA – Right. And they’re wonderful people, when you find good ones.

CYNTHIA – Yeah. I mean, I think that caregiving is just such an intimate activity, right? That this person’s helping your spouse in the shower and the toilet, and it takes some getting used to.

JANA – Yeah. So Cynthia, you had your own medical scare? That must have been terrifying. I mean it would be even without Perry’s injury.

CYNTHIA – Yeah, yeah, I had these cysts on my ovaries, and we weren’t sure what it was. And I, you know, at the time, I was just still so sick in the whole – worrying about Perry all the time, and his caregiving and his classes and that sort of thing that I was just thrown for a loop. It’s like, Oh, my God, like, I can’t have something happened to me now. So, but it turned out, okay. And my family totally rallied around that. So as soon as I heard that I was going to have surgery, you know, the boys came home. My aunt was here, my sister came, so I was very well taken care of, but it was a really big scare, because it was like, you know, when you’re the caregiver, you always wonder like, What if something happens to me? Then what’s gonna happen? Who’s gonna take care of him? How is this going to work?

JANA – Mm-hmm. Of course, because I lived in LA, a lot of the references resonated for me. In particular, when you went shopping at the Century City Mall, and Perry disappeared.

CYNTHIA – Oh… yeah. You know there were some chapters that were very, very hard to write. That one I almost didn’t include, but my son Zach said, That’s part of the experience, you have to include that. But it was such a horrific thing. And I think any – it is the worst nightmare for anyone that’s a caregiver, right? That the person you’re caring for disappears. And so unexpected, because like I said, his balance was really off and he, like, I would sit him in a chair and he would never get up. And I don’t know what happened that day where he got up, but it was just that sense of panic that you feel, like that person is not where they’re supposed to be. And where in the world could they be? It was so frightening.

JANA – Mm-mm. And then he was found hours later.

CYNTHIA – Yeah, he was found on someone’s lawn and they had taken him to the hospital. Thank goodness. So… yeah.

JANA – Oh, my gosh, plagued by guilt. I think probably every caregiver has gone through that experience where they feel plagued by guilt that you failed the person.

CYNTHIA – Yeah.

JANA – And it was a reminder for you that you could never let your guard down. But you could control this. So that’s an interesting sort of spin on it, too, because you are reminded of that fact, that you can never let your guard down because, you know, of this experience. On the other hand, you could control it. So how did you learn to control that?

CYNTHIA – Well, we just, we just made sure that there was somebody with him all the time, I thought about getting one of those medic bracelets or something that he would wear, but he never wore jewelry. I mean, the whole time that we were together. He begrudgingly had to wear a watch for work, but the minute he came home, he took it off. When he was in the hospital, he used to tear off all his – the tags, you know, that they put on your arm. So I knew I couldn’t hang anything on him, cuz he would just take it off.

CYNTHIA – So we started to put a fake wallet in his pocket. So I made a copy of his ID and a little card that said, you know, I’m brain injured, with contact information. So we resorted to that. To like this fake ID and having something on him. But then I think we just became – me and the caregiver – we just became ever vigilant. Like, Don’t ever let him leave your sight, you know?

JANA – Yeah. So I want to talk about the book a little bit more specifically, and how long it took you to actually put pen to paper. I know you were journaling lot. But I wonder how long it took you to put this together? Because you know, writing about loss is really hard.

CYNTHIA – Yeah, I think I started actually crafting stories, you know, or essays, probably five or six years later. Because I think you need some distance from it, to be able to write about it. So I started taking classes at UCLA extension – classes and writers’ studios there. And I fell into a group of fellow writers. We formed a writing group, I think back in 2008. 2007, 2008. And through them, I really was able to craft this book, because there’s the story and then there’s the writing of the story.

CYNTHIA – And what I had to learn was how to write the story. To make it compelling, right? And to have a beginning, middle and end, and that sort of thing. So my writers group, we meet every month, and we have been for like the last 10 years. We’ve met every month, and you have to bring something to workshop. You can’t just come and listen to other people read, you have to bring something of your own. And then we critique each other’s work. So that was really helpful, because I think otherwise, it’ll just be like a spilling the facts, like, you know, this happened and then this happened. So I really credit that writers group, that helped craft each of the chapters into a story.

JANA – And probably helped you with revisiting the actual events, because that must have been very emotional.

CYNTHIA – Yes. You know, people always ask, was it cathartic to write this? And I say, No, because you had to revisit – you know, you had to revisit the panic, you had to revisit the pain of that moment, to make it become real on the page.

JANA – Yeah.

CYNTHIA – And it’s hard. It’s just like that chapter at the mall. That was so, so hard to write.

JANA – I can imagine. But I’m so glad you wrote it, because it’s so emotionally honest. And I also really appreciated the passage that you referred to earlier, where someone said, God doesn’t give you more you can handle. Because the anger there is palpable, and you have moments of anger.

CYNTHIA – Yeah, yeah. And there were, you know, there are those moments too at night when I was working full-time. I mean, I’m retired now, but when I was working full-time and he’d wake in the middle of the night, and he’d have these agitation periods. Not wild or crazy or anything, but just not able to sleep. And he would toss and turn, or sit up in the bed, or get up and try to walk somewhere, that were just so infuriating. Because I knew the alarm would go off at 6:30 in the morning and I’d have to get up and have a full day in meetings. And it was like, can you please just sleep for another couple of hours? Or can you please just go back to sleep? So I wanted to capture those moments that caregivers experience of, like, achhhh… is this ever going to end? You know? Those parts are really hard to write, too.

JANA – Yeah, I was happy to read that you were able to get away. Could you talk about the importance of that trip to Istanbul that you took?

CYNTHIA – Yeah, well, my younger son offered to stay with my husband while I traveled to Istanbul with my older son. And it was just this total freeing experience for me, and a reminder that I’m not the one that’s brain injured, I still have dreams of travel, I still have this life to live. And I don’t have to spend every moment being the caregiver and being the responsible one for my husband. That, you know, he’ll be fine if I leave. But I think it’s so hard for caregivers to give themselves permission to do that. And it took me a long time to get to that point to say, Oh, it’s okay if I pay the caregiver to stay with my husband, while I do something else other than work, like, you know, while I go get a massage, or a while I go shopping, because I still have to take care of myself too. And I think that’s so hard to do, you know, to give yourself permission to do that.

JANA – Why do you think it’s so hard?

CYNTHIA – Because I think as a caregiver, you feel like you’re so responsible for that person. And if you’re not there, they’re not going to be taken care of or something, you know? I don’t know. For me, it was – for me, it was really hard to give myself permission to do that. And then once I did… so once I did take that trip to Istanbul, and realized, wow, you know, I could have this whole other existence too, that doesn’t mean I’m forever having to be at home with my husband. And I could go to places that are really hard to travel with him. And I could do it on my own. So yeah, that was a total revelation.

JANA – Well, for people who don’t have the option of getting away, or they have a different setup, let’s say maybe they don’t have a son, they don’t have someone, I wonder if you would suggest what you can do to take care of yourself, if you can’t get away.

CYNTHIA – Yeah, just set aside some time to yourself. I mean, if you do have a caregiver with your loved one, anyway, just an hour of just doing an activity YOU like. Like, read a book that you want to read, or you know, just do something else – watch a show that only you want to watch. I also found, there was a Caregiver Resource Center in Los Angeles that gave me a respite grant. You know, there was like this very long waiting list, and it came as a total surprise.

CYNTHIA – But you know, I just got a call one day out of the blue that said, Hey, you name’s at the top of the list, and we’re going to give you this money to spend on yourself. So you could use it to pay for a caregiver while you take a weekend off on your own, or you could use it to help defray your caregiver costs, but it’s intended for you. And it wasn’t the money so much. It was just the fact that someone’s giving you the permission, you know, to use this money for something on yourself.

JANA – And acknowledge your hard work. So, 10 years into the work of caregiving, you wrote, “Other than work and caregiving, what was the shape of my life now?” I appreciated it so much that you – you, Cynthia – that you were assessing yourself so objectively. And perhaps in the moment you were less able to make that assessment than you were years later, when you started crafting the book, but I thought that was a really beautiful idea of even looking at the shape of your life, because your life is reshaped through caregiving.

CYNTHIA – Yeah. And I think at that time, I was thinking about my younger self, you know, my 20s, and all these dreams that we had in our 20s, that we would retire, we would travel the world, we would take up all these crafts in the garage, and, you know, have this really kind of peaceful life together. And it so did not turn out that way. So it was kind of like a reshaping of what your dreams are for what you envision for your life, you know?

JANA – Mm-hmm. You lost a big part of him. But in the reading of this, I absolutely got the sense that there was still so much love. And that struck me as being something to hold on to. To cling to, really.

CYNTHIA – Yeah, I think it would have been a very different story if he didn’t recognize us or didn’t still have that capacity for love, for his family, and for me. It would have been very different.

JANA – Yeah. So the injury was in 2003. And for listeners, we would like to acknowledge that Perry passed away this year, in April. So it was 15 years of caregiving. And now you’re remaking your life, Cynthia, in another new way, right?

CYNTHIA – Yeah, yeah. It’s just – it’s like a double loss, because the book is really about losing him pre-brain injury, or losing what he was pre-brain injury and learning to love what emerged post-brain injury. So, so like, you know, we went through all this trauma, all these trials together, and then to lose him suddenly in April was like a double loss. Because, you know, it’s like, you mourn the pre-brain injury person, you mourn the post-brain injury person.

CYNTHIA – And it sounds so strange, because, you know, the whole time when I was in the whole caregiving mode, there were times where – and I write about this in the book – where you just wish for it to end. And I remember thinking, like, how much longer am I going to be doing this? Am I going to be doing this in my 70s and 80s? Or 90s? Right? And what happens when I’m too old to be able to care for him in this way?

CYNTHIA – So you know, I used to think those thoughts like, Oh, gosh, you know, how much longer? And I wish I didn’t have to do this. And then when he passed away, it’s like, I would give back any of that, just to have him back. The caregiving was an inconvenience, but boy, the emptiness of not having him here is so much worse than the worst parts of caregiving, you know?

JANA – Can you even imagine what’s next for you? Or are you just not thinking that far ahead?

CYNTHIA – No. I think I’m still kind of trying to discover like, What now? You know, I realized so much my energy was tied up into caregiving. So it’s like, what do I do with all that energy now?

JANA – Yeah, it’s just different.

CYNTHIA – It is. It’s really different. I mean, you know, I quit work like a year ago, and I had these ideas that oh, we can go to our place in Mammoth, and we could take all these road trips together. Or, you know, we just can enjoy each other now that I’m not all stressful from work.

JANA – And you could still enjoy each other, because you still had him. Even though he was, you know, disabled, you could still enjoy each other.

CYNTHIA – Yeah. And he was so happy that I was at home.

JANA – Yeah, I’ll bet.

CYNTHIA – Because I was gone from, you know, seven in the morning til seven at night when I worked. It was really nice. So I – yeah, these past few months I’m just kind of wondering, Okay, what do I do now?

JANA – I know, you’ll figure it out. Cynthia, I wonder what you want readers to take away from this book?

CYNTHIA – Well, you know, I wrote it for, kind of two primary audiences. One is people in the medical community, so that they could see, this is what families go through, and hope that they have a little bit more compassion when they’re dealing with families like this, and that the other families won’t have the same experience that I had, where they’re basically saying, Okay, here’s your brain injured husband, see you later. You know, you figure it out. I mean, it would be so nice if people in the medical community would at least acknowledge what families are going through. And maybe you know, once in a while, ask – like, How are you dealing with this? And how can we, in the medical community, be of help to you? To the families, and not just the patient.

CYNTHIA – And the other audience, was for other caregivers, because as I was going through this, it was a very lonely experience. And I felt guilt every time I didn’t want to be in this role. And I’d always think, I am not as kind as other caregivers, because I have these moments where I just resisted this role and wished that it would be over. But I think all caregivers feel that way, you know? And I had looked for a book like this when this happened to my husband, because I wanted to know, well, how do families deal with this? How do they get the strength to just keep going? Or, you know, do you just shut yourself off to the world?

JANA – Yeah, and it’s a very specific injury. I haven’t read a book like this before. And I’ve read a lot of books for the interviews I’ve done. And it was a really worthwhile endeavor. And it was very, very well written. So I want to just say I really enjoyed it. We’ve been speaking with author Cynthia Lim about her book, “Wherever You Are: A Memoir of Love, Marriage and Brain Injury.” This book pulls you in right from the start. It’s accessible, it’s well-written and it doesn’t pull any punches. In other words, it’s real. We’re going to have links on the Agewyz website to Cynthia’s book, her website and her Facebook page so you can connect with her and learn more about her work. Cynthia, thank you so much for being on the show. And thank you for writing this book. I mean it sincerely when I say I truly enjoyed it, and I want everyone to go out and buy it. “Wherever You Are: A Memoir of Love, Marriage and Brain Injury.” Thank you, Cynthia.

CYNTHIA – Thank you so much.

Get the first 30 pages of Jana’s book, Scattered, her own personal story of caregiving.

Scattered: My Year As An Accidental Caregiver is available in paperback and eBook at Amazon.com.

Scattered: My Year As An Accidental Caregiver is available in paperback and eBook at Amazon.com.INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT:

JANA PANARITES (HOST) – Cynthia Lim thought she had the perfect life. A loving husband who was also a successful lawyer, her own fulfilling career in education, two sons thriving in high school, and a home in Los Angeles filled with books, music and art. It all changed in June of 2003 when Cynthia’s husband of 20 years suffered a cardiac arrest, which then led to what’s called anoxic brain injury. After the injury, Cynthia wrote about her experience of caring for her husband, Perry, and herself in a memoir titled, “Wherever You Are: A Memoir of Love, Marriage and Brain Injury.” It’s a story of reinvention and reimagining life with disability. Cynthia Lim recently retired as the Executive Director for Data and Accountability for the Los Angeles Unified School District. She’s been featured on KRCB’S “A Novel Idea,” on the NPR podcast, and her essays have appeared in Hope magazine, Kaleidoscope and Witness magazine, among other publications. Cynthia joins us today from Los Angeles, where she’s lived with her family for the past 30 years. Cynthia, welcome to The Agewyz Podcast.

CYNTHIA LIM – Thank you so much for having me.

JANA – Well, I’d love to put this in context for our listeners. I know, you grew up in Salinas, California and your husband, Perry grew up in Torrance, which was worlds away – culturally, I should say, maybe not really physically. And I really appreciated that sort of differentiation in the book. Can you tell us how you met and a little bit about your upbringing and your environment versus his?

CYNTHIA – Yes. So we met at UC Santa Barbara, on the first day of college, actually. We were standing in line to register our bikes. And we, you know, fell into a conversation. So I grew up in this very traditional Chinese family in Salinas. My parents were grocers. So I had a very, kind of sheltered upbringing, you know, didn’t really know much about big city life or arts and culture and that sort thing, especially Western culture, because my parents were immigrants, and we spoke Chinese in my house.

CYNTHIA – And Perry was, you know, from the LA area, he’s from a suburb of Los Angeles. But to me, he seemed really worldly. I mean, he had done all these things and taken advantage of living in the big city and was culturally aware and he was just so different. And his background, he came from a Jewish family that wasn’t very observant, but, you know, in Salinas I had never met anyone Jewish. So it was kind of this meeting of two very different cultures. And that’s what made him, I think, so interesting and appealing to me. It’s like, here’s somebody that was so different from the world I grew up in.

JANA – And you really drew that picture, so clearly. I really had that sense, in the book. You really captured that so well. So you had this perfect life. Beyond what I described in the intro, what did that look like for you? Paint the picture for us.

CYNTHIA – Well, you know, we were struggling college students together. And after, undergraduate school, we joined VISTA. We were VISTA volunteers in the Midwest and living on poverty wages. You know, VISTA’s like the Peace Corps, but internal – in the United States. So we really had, like, nothing. And, you know, we got student loans to get through graduate school, and we get out of graduate school, we land these jobs, it’s – you know, finally paying the salaries after all these years. So, you know, maybe to others, it wouldn’t seem like – we didn’t have that much, but to us it was like, Wow! You know, both of us earning full salaries, we thought, Wow, this is a really luxurious lifestyle.

JANA – Two salaries – woo hoo!

CYNTHIA – Right. As opposed to, you know, student wages or VISTA volunteer wages. And you know, from there, we bought a house, we had two sons, and Perry had this philosophy of, you know, working really hard and playing really hard. So he made partner early in his law firm. And he worked very hard as a, he was a corporate bankruptcy attorney. But he also would really relish, like, the time that we had together as a family.

CYNTHIA – And so any time the kids were on spring break, or in the summer, he would plan these vacations so that we would always go backpacking in the mountains, in the Sierra Nevada, here in California, or he would plan, you know, some exotic vacation somewhere. So he really relished the time together, that we had as a family because I think he felt like, you know, the kids are only going to be young once. And we need to set aside the time and spend with them. And so our sons were teenagers at the time of his heart attack. They were 15 and 18. Our oldest son had just graduated high school, and was going to go off to college in the Fall, when he had his heart attack. So… that changed everything.

JANA – And that was a very dramatic scene, that the book begins with and the reader – as a reader, I was just drawn right in from the very beginning. So the book opens up with a dramatic scene that takes place in a Portland hotel room. You and your husband had gone on a weekend in June. Cynthia, I know this is probably hard for you to talk about. But can you tell us what memories you have of that event?

CYNTHIA – It was just a blur. You know, it’s one of those things where you think, what’s the worst thing that can happen? And then it happens. And everything, you know, everything that people tell you like CPR, or, you know, what to do in an emergency? It’s like, my mind just went blank. It’s like I could not remember any of those things. It’s this sense of panic that I hope that no one will ever have to experience because you’re just like, paralyzed. You’re just like, Oh, my God, what do I do? What do I do? And you know that there’s something you should be doing, but you can’t – I couldn’t conjure it up. Like, what is it I’m supposed to be doing? What were all those lessons that we took, and you know, it was just sheer panic.

JANA – And you had to absorb a lot of information really fast. Your doctor said that Perry needed a stent, or he’ll die and you had to consider the risks of surgery, and then the boys are arriving. Wow, I believe that it’s a blur. Because I know that when my father died – he died suddenly – and that period is a blur for me. So whatever else you remember from the event before he came home, I wonder if you could share some of that with us?

CYNTHIA – Yeah, well, you know, I kept – I am a journal keeper. You know, I’ve been keeping a journal since high school. And it was a way of calming myself to just write, in the midst of all this. So I just remember being in the emergency room in the hospital, in Portland, not knowing what was going on. Our kids were on a plane, you know, headed to Portland. I didn’t know if he was alive or, you know, what the deal was. We just, we arrived at the hospital, they whisked him away and they put me in this room. And so I just jotted things there. Like, I don’t even know what’s happening. You know, my feet were cold. Those kinds of things.

CYNTHIA – And throughout his whole time in the hospital – he was in Portland for two weeks in a coma, then we were able to transport him back to Los Angeles. He was still in a coma for probably a few days. And then he woke. And he was in the hospital for like, another month. And he went to a rehab hospital. And then he went to this residential facility. So throughout that time, all this new information is just being thrown at you. I’m interacting with all these doctors and therapists and nurses and not really knowing, you know, what’s what. So writing was my way of just organizing my thoughts. And so a lot of the book about those parts were really drawn from what I had written and remembered in my journal, because I knew five, six years later, I would not be able to remember all those details.

JANA – Well, spousal caregiving is so unique to begin with, let alone after a traumatic event like this. I know that it was not the retirement that you envisioned. One day, you know, you’re on an equal playing with your partner, and then it’s completely upside down. I wonder if you could talk a little bit about what it was like for you, being a caregiver for Perry and how it evolved. And if you want to refer to any examples from what you remember, feel free to.

CYNTHIA – Yeah. You know, I think initially, it was really frightening, I think when you’re a caregiver of someone with a brain injury. Because at the period when he first woke through his coma, you know, I’m expecting that he’s going to be the same person and the same voice and have the same memories. And what would happen in his brain is – with anoxic brain injury, it’s like it’s diffused throughout your brain, it’s not one part of your brain that’s damaged, and then other parts, you know, compensate for it. So in his case, it’s like every part of his brain was a little bit damaged.

CYNTHIA – And so his speech at first came back in whispers, so he wasn’t speaking into his normal voice. And then he didn’t initiate speech. So if you were sitting together, he wouldn’t say, you know, how are you doing today? Or, you know, what’s happening? He was very passive. So he would understand everything that was said to him, but he wouldn’t initiate speech.

CYNTHIA – And initially, when he woke up from his coma, he went through this agitation phase. I think every brain injury patient goes through that, where their mind’s just kind of a jumble. And they’re trying to make sense of things. And so that part was the most frightening because he was this person they didn’t recognize. And when he was in the rehabilitation hospital, that’s where it was the worst. So he would walk into other patients’ rooms and, you know, say he was searching for a phone or something, just not making sense. And I would have to be there and the nurses would be there. We tried to get him back in his room.

CYNTHIA – It’s just really frightening because physically, he’s still looked like my husband, but mentally, it was like, I don’t know who this person is. And I don’t know how I would deal with this. And then he went through this phase where he was taken off his clothes, and I was thinking, Oh, my God, what, what am I gonna do when I take him home and he does that? I won’t be able to go out in public anywhere with him. So it was a very, very frightening experience. And I imagine it’s probably what a lot of spouses go through if your spouse has dementia or Alzheimer’s, you know, where their mind is just not making sense.

JANA – I thought it was interesting that you wrote, “He wasn’t aware of his deficits. He thought he could manage, but he couldn’t.”

CYNTHIA – Yeah. And in a way, it was almost a blessing that he wasn’t aware of his deficits, because I think if he was aware, maybe he would have felt the same sense of sorrow and sadness that we did. But yeah, he – there’s even a term for it in the, in the disability literature. They call it “anosognosia” or something where, you know, if you asked him, he would say, Oh, yeah, I can walk from here to, you know, to the pier, or I can hike this trail. And then and, you know, physically he can’t. But it didn’t seem to bother him that he couldn’t.

JANA – You had this period of constantly feeding hospital parking lot meters, being at the hospital. And your, your son, Zach eventually said, Mom, you need to go back to work. I wonder if you could talk about the isolation you felt and being cut off and then going back to work?

CYNTHIA – Yeah, it’s such a, it is such an isolating experience. You know, that first month or so afterwards, where your entire life is being in the hospital, sitting next to his bed, monitoring every nurse, every medical interaction, and that becomes your world. And it was just a strange existence, where the only people you’re interacting with, it has to do with illness and disability and medical doctors. And I wasn’t even aware of the effect that it had on me. But, you know, I was looking really horrible, then. I wasn’t eating properly, I wasn’t exercising.

CYNTHIA – And stepping back into work, the hardest part was, you know, facing everybody that wants to talk to you and ask and, you know, you have to tell and retell the story. But once I got into the work, I found it’s so comforting, because it was this affirmation that I had another life other than disability, and other than my spouse’s disability – that I wasn’t the one that was brain injured, and I still had a life. So I think that was the very first step in acknowledging that, as a caregiver, you have to like pay attention to your own life. You can’t just immerse yourself in your spouse and that illness.

JANA – Yeah, you learned a lot about what to say and what not to say to someone going through a catastrophic experience. I thought you did a great job of highlighting some of the crazy questions and comments that you had to field. People often want to say the right thing, but they don’t really have the language for it.

CYNTHIA – Yeah. And I think that, you know, people really do care and they don’t know what to say. But there are some things that are, like, you should not say.

JANA – Such as?

CYNTHIA – Well, I, you know, I, I used to hate it when people would say, Well, you know, God doesn’t give you more than you can handle. I would think. that is like the stupidest thing to say. What are you saying? That somehow I deserve to get more than somebody else? I mean, you know, I don’t know. It’s just, it’s just such a bizarre thing to say to someone.

JANA – I guess that’s a coping mechanism for the person who says that, too, because they just don’t know what else to say. I don’t know. I won’t get too deep into that, but

CYNTHIA – Yeah. [both laugh]

JANA – So your son thought about – your son Zach thought about delaying college, while Perry was still being hospitalized, I think, or even maybe at this point he was at Casa Colina.

CYNTHIA – Yeah.

JANA – But you said, No. Why was it so important to you that he get on with his life?

CYNTHIA – Well, so my, my father passed away when I was seven. He was killed in a plane crash. And my mother was left with five kids and a business. And you know, she was an immigrant, she didn’t speak English. And from that point on, she totally depended on her children to help her through life, basically. You know, we had to translate for her. And we felt this tremendous responsibility for her throughout our adult lives, you know, because she was this helpless widow. And I didn’t want my sons to go through that. I wanted them to live their lives without guilt, and not feel like they had to stay at home, take care of me, or that I was dependent on them. I just remember what it felt like for me to go away to college – that sense of freedom that I felt, being a freshman in college and being with this whole cohort of kids starting school at the same time, and I really wanted him to have that same experience.

JANA – Mm-hmm. And then you went to orientation with Zach, without Perry.

CYNTHIA – Yeah. All those things, I think all those things that you used to do as a couple, but then you have to do alone? They were so hard, you know, because you depend on your spouse so much to share your thoughts, and especially something like that, so emotional, as you know, your first kid going to college. It’s just such an emotional thing.

JANA – Yeah. So Zach went to NYU. And you came back and you were working full time and visiting Perry at rehab. How did you manage that?

CYNTHIA – You know, I look back now and I think, How DID I manage that? I don’t know. I think you know, when you’re in the midst of it, you just put your head down and you do it. And you don’t even think. I don’t think I had much else in my life other than going to work, visiting Perry, and then making sure that Paul, my younger son, was taken care of at home too. So, it was so much that I just, I don’t even think I could think about it. I just did it, you know?

JANA – Mm-hmm. I really appreciated the passage where you had that sobering conversation with the intake person, Lisa, explaining, This is how insurance works. I mean, that was really, really helpful. Maybe you can talk about that a little bit – the shock of that conversation.

CYNTHIA – Yeah. Unless you need to use it nobody really tells you, this is how insurance works. And so I was so bent on just bringing him home, you know, because I was so convinced that the best place for my husband was at home, where we could take care of him. And this intake counselor was trying to convince me to send him to a residential treatment facility. Because most health insurance companies, they have a benefit that they call – it’s like a nursing home facility benefit, where they pay- well, mine paid up to 100 days. And she said if you don’t use it, it just goes away. And you can only use it if you’re moving a patient from a rehab facility to a nursing home. If I brought him home and then decided, like, Oh, I can’t handle it, he has to go to a nursing home, I wouldn’t be able to place him there because he had to come from an acute medical facility to a nursing home, which – I’m like, how many people know that?

JANA – I wouldn’t have known that. Is that standard, with all insurance plans?

CYNTHIA – I think so.

JANA – I think it is.

CYNTHIA – So it was like this mystery to me. Like, my experience with the medical community up to this was, you know, having babies in the hospital, which is like a really happy thing. So you’re faced with these neurologists, and these therapists and some of them are just really dour and pessimistic. And they don’t give you any sense of hope.

JANA – Yeah, you gave up on the medical community after a certain point. You know, you stepped away from Western medicine. Tell us how that worked out.

CYNTHIA – Well, you know, it was so limited. And I think especially for brain injuries, the common thought in the medical community is that after a year, there’s no more improvement. And in Perry’s case, I think they paid for maybe like three or four months after he came home. So that was within a year of his brain injury. And one of his speech therapists wrote something in his notes, like he thought Perry had plateaued. And that was enough to trigger up and down the chain, like – Oh, there’s no more improvement in this case, further therapy isn’t going to do any good.

CYNTHIA – And so they just cut off physical speech, occupational therapy. And I was incredulous. I was like, How could you do that? Like, what am I supposed to do now? It wasn’t even a year after his brain injury, and I’m just – I’m getting used to having a caregiver in my house while I’m gone. How we supposed to fill up his days? Like, what do families do? And they weren’t very helpful at all.

JANA – And what did you do?

CYNTHIA – In my spare time, I searched the internet for anything about caregiving in Los Angeles, classes for brain injury. I heard about something from the Stroke Association. Even though he didn’t have a stroke, a lot of his symptoms were like post-stroke. And so I just had to become like this advocate, searching the Los Angeles area for any kinds of classes.

CYNTHIA – So I contacted hospitals, I contacted, like I said, the Stroke Association, and I found this wonderful, wonderful class at our local community college, for acquired brain injury. And that was a lifesaver, because they had exercise classes, they had speech classes and computer classes for people like Perry that were brain injured. And so that was a total, total find.

JANA – Yeah, I really appreciated the passage where you talked about getting used to having lots of people in your house, and your house wasn’t your own. My mom lives with my sister and my sister works full-time, so we have a team of caregivers, and my sister feels like her home has become a hotel.

CYNTHIA – Yeah. You know, I think caregivers have to get used to that. Just the fact that there’s like another person in your life. And it, it’s like a very intimate person that’s, you know, helping your loved one with bathing.

JANA – Right. And they’re wonderful people, when you find good ones.

CYNTHIA – Yeah. I mean, I think that caregiving is just such an intimate activity, right? That this person’s helping your spouse in the shower and the toilet, and it takes some getting used to.

JANA – Yeah. So Cynthia, you had your own medical scare? That must have been terrifying. I mean it would be even without Perry’s injury.

CYNTHIA – Yeah, yeah, I had these cysts on my ovaries, and we weren’t sure what it was. And I, you know, at the time, I was just still so sick in the whole – worrying about Perry all the time, and his caregiving and his classes and that sort of thing that I was just thrown for a loop. It’s like, Oh, my God, like, I can’t have something happened to me now. So, but it turned out, okay. And my family totally rallied around that. So as soon as I heard that I was going to have surgery, you know, the boys came home. My aunt was here, my sister came, so I was very well taken care of, but it was a really big scare, because it was like, you know, when you’re the caregiver, you always wonder like, What if something happens to me? Then what’s gonna happen? Who’s gonna take care of him? How is this going to work?

JANA – Mm-hmm. Of course, because I lived in LA, a lot of the references resonated for me. In particular, when you went shopping at the Century City Mall, and Perry disappeared.

CYNTHIA – Oh… yeah. You know there were some chapters that were very, very hard to write. That one I almost didn’t include, but my son Zach said, That’s part of the experience, you have to include that. But it was such a horrific thing. And I think any – it is the worst nightmare for anyone that’s a caregiver, right? That the person you’re caring for disappears. And so unexpected, because like I said, his balance was really off and he, like, I would sit him in a chair and he would never get up. And I don’t know what happened that day where he got up, but it was just that sense of panic that you feel, like that person is not where they’re supposed to be. And where in the world could they be? It was so frightening.

JANA – Mm-mm. And then he was found hours later.

CYNTHIA – Yeah, he was found on someone’s lawn and they had taken him to the hospital. Thank goodness. So… yeah.

JANA – Oh, my gosh, plagued by guilt. I think probably every caregiver has gone through that experience where they feel plagued by guilt that you failed the person.

CYNTHIA – Yeah.

JANA – And it was a reminder for you that you could never let your guard down. But you could control this. So that’s an interesting sort of spin on it, too, because you are reminded of that fact, that you can never let your guard down because, you know, of this experience. On the other hand, you could control it. So how did you learn to control that?

CYNTHIA – Well, we just, we just made sure that there was somebody with him all the time, I thought about getting one of those medic bracelets or something that he would wear, but he never wore jewelry. I mean, the whole time that we were together. He begrudgingly had to wear a watch for work, but the minute he came home, he took it off. When he was in the hospital, he used to tear off all his – the tags, you know, that they put on your arm. So I knew I couldn’t hang anything on him, cuz he would just take it off.

CYNTHIA – So we started to put a fake wallet in his pocket. So I made a copy of his ID and a little card that said, you know, I’m brain injured, with contact information. So we resorted to that. To like this fake ID and having something on him. But then I think we just became – me and the caregiver – we just became ever vigilant. Like, Don’t ever let him leave your sight, you know?

JANA – Yeah. So I want to talk about the book a little bit more specifically, and how long it took you to actually put pen to paper. I know you were journaling lot. But I wonder how long it took you to put this together? Because you know, writing about loss is really hard.

CYNTHIA – Yeah, I think I started actually crafting stories, you know, or essays, probably five or six years later. Because I think you need some distance from it, to be able to write about it. So I started taking classes at UCLA extension – classes and writers’ studios there. And I fell into a group of fellow writers. We formed a writing group, I think back in 2008. 2007, 2008. And through them, I really was able to craft this book, because there’s the story and then there’s the writing of the story.

CYNTHIA – And what I had to learn was how to write the story. To make it compelling, right? And to have a beginning, middle and end, and that sort of thing. So my writers group, we meet every month, and we have been for like the last 10 years. We’ve met every month, and you have to bring something to workshop. You can’t just come and listen to other people read, you have to bring something of your own. And then we critique each other’s work. So that was really helpful, because I think otherwise, it’ll just be like a spilling the facts, like, you know, this happened and then this happened. So I really credit that writers group, that helped craft each of the chapters into a story.

JANA – And probably helped you with revisiting the actual events, because that must have been very emotional.

CYNTHIA – Yes. You know, people always ask, was it cathartic to write this? And I say, No, because you had to revisit – you know, you had to revisit the panic, you had to revisit the pain of that moment, to make it become real on the page.

JANA – Yeah.

CYNTHIA – And it’s hard. It’s just like that chapter at the mall. That was so, so hard to write.

JANA – I can imagine. But I’m so glad you wrote it, because it’s so emotionally honest. And I also really appreciated the passage that you referred to earlier, where someone said, God doesn’t give you more you can handle. Because the anger there is palpable, and you have moments of anger.

CYNTHIA – Yeah, yeah. And there were, you know, there are those moments too at night when I was working full-time. I mean, I’m retired now, but when I was working full-time and he’d wake in the middle of the night, and he’d have these agitation periods. Not wild or crazy or anything, but just not able to sleep. And he would toss and turn, or sit up in the bed, or get up and try to walk somewhere, that were just so infuriating. Because I knew the alarm would go off at 6:30 in the morning and I’d have to get up and have a full day in meetings. And it was like, can you please just sleep for another couple of hours? Or can you please just go back to sleep? So I wanted to capture those moments that caregivers experience of, like, achhhh… is this ever going to end? You know? Those parts are really hard to write, too.

JANA – Yeah, I was happy to read that you were able to get away. Could you talk about the importance of that trip to Istanbul that you took?

CYNTHIA – Yeah, well, my younger son offered to stay with my husband while I traveled to Istanbul with my older son. And it was just this total freeing experience for me, and a reminder that I’m not the one that’s brain injured, I still have dreams of travel, I still have this life to live. And I don’t have to spend every moment being the caregiver and being the responsible one for my husband. That, you know, he’ll be fine if I leave. But I think it’s so hard for caregivers to give themselves permission to do that. And it took me a long time to get to that point to say, Oh, it’s okay if I pay the caregiver to stay with my husband, while I do something else other than work, like, you know, while I go get a massage, or a while I go shopping, because I still have to take care of myself too. And I think that’s so hard to do, you know, to give yourself permission to do that.

JANA – Why do you think it’s so hard?

CYNTHIA – Because I think as a caregiver, you feel like you’re so responsible for that person. And if you’re not there, they’re not going to be taken care of or something, you know? I don’t know. For me, it was – for me, it was really hard to give myself permission to do that. And then once I did… so once I did take that trip to Istanbul, and realized, wow, you know, I could have this whole other existence too, that doesn’t mean I’m forever having to be at home with my husband. And I could go to places that are really hard to travel with him. And I could do it on my own. So yeah, that was a total revelation.

JANA – Well, for people who don’t have the option of getting away, or they have a different setup, let’s say maybe they don’t have a son, they don’t have someone, I wonder if you would suggest what you can do to take care of yourself, if you can’t get away.

CYNTHIA – Yeah, just set aside some time to yourself. I mean, if you do have a caregiver with your loved one, anyway, just an hour of just doing an activity YOU like. Like, read a book that you want to read, or you know, just do something else – watch a show that only you want to watch. I also found, there was a Caregiver Resource Center in Los Angeles that gave me a respite grant. You know, there was like this very long waiting list, and it came as a total surprise.

CYNTHIA – But you know, I just got a call one day out of the blue that said, Hey, you name’s at the top of the list, and we’re going to give you this money to spend on yourself. So you could use it to pay for a caregiver while you take a weekend off on your own, or you could use it to help defray your caregiver costs, but it’s intended for you. And it wasn’t the money so much. It was just the fact that someone’s giving you the permission, you know, to use this money for something on yourself.

JANA – And acknowledge your hard work. So, 10 years into the work of caregiving, you wrote, “Other than work and caregiving, what was the shape of my life now?” I appreciated it so much that you – you, Cynthia – that you were assessing yourself so objectively. And perhaps in the moment you were less able to make that assessment than you were years later, when you started crafting the book, but I thought that was a really beautiful idea of even looking at the shape of your life, because your life is reshaped through caregiving.

CYNTHIA – Yeah. And I think at that time, I was thinking about my younger self, you know, my 20s, and all these dreams that we had in our 20s, that we would retire, we would travel the world, we would take up all these crafts in the garage, and, you know, have this really kind of peaceful life together. And it so did not turn out that way. So it was kind of like a reshaping of what your dreams are for what you envision for your life, you know?

JANA – Mm-hmm. You lost a big part of him. But in the reading of this, I absolutely got the sense that there was still so much love. And that struck me as being something to hold on to. To cling to, really.

CYNTHIA – Yeah, I think it would have been a very different story if he didn’t recognize us or didn’t still have that capacity for love, for his family, and for me. It would have been very different.

JANA – Yeah. So the injury was in 2003. And for listeners, we would like to acknowledge that Perry passed away this year, in April. So it was 15 years of caregiving. And now you’re remaking your life, Cynthia, in another new way, right?

CYNTHIA – Yeah, yeah. It’s just – it’s like a double loss, because the book is really about losing him pre-brain injury, or losing what he was pre-brain injury and learning to love what emerged post-brain injury. So, so like, you know, we went through all this trauma, all these trials together, and then to lose him suddenly in April was like a double loss. Because, you know, it’s like, you mourn the pre-brain injury person, you mourn the post-brain injury person.

CYNTHIA – And it sounds so strange, because, you know, the whole time when I was in the whole caregiving mode, there were times where – and I write about this in the book – where you just wish for it to end. And I remember thinking, like, how much longer am I going to be doing this? Am I going to be doing this in my 70s and 80s? Or 90s? Right? And what happens when I’m too old to be able to care for him in this way?

CYNTHIA – So you know, I used to think those thoughts like, Oh, gosh, you know, how much longer? And I wish I didn’t have to do this. And then when he passed away, it’s like, I would give back any of that, just to have him back. The caregiving was an inconvenience, but boy, the emptiness of not having him here is so much worse than the worst parts of caregiving, you know?

JANA – Can you even imagine what’s next for you? Or are you just not thinking that far ahead?

CYNTHIA – No. I think I’m still kind of trying to discover like, What now? You know, I realized so much my energy was tied up into caregiving. So it’s like, what do I do with all that energy now?

JANA – Yeah, it’s just different.

CYNTHIA – It is. It’s really different. I mean, you know, I quit work like a year ago, and I had these ideas that oh, we can go to our place in Mammoth, and we could take all these road trips together. Or, you know, we just can enjoy each other now that I’m not all stressful from work.

JANA – And you could still enjoy each other, because you still had him. Even though he was, you know, disabled, you could still enjoy each other.

CYNTHIA – Yeah. And he was so happy that I was at home.

JANA – Yeah, I’ll bet.

CYNTHIA – Because I was gone from, you know, seven in the morning til seven at night when I worked. It was really nice. So I – yeah, these past few months I’m just kind of wondering, Okay, what do I do now?

JANA – I know, you’ll figure it out. Cynthia, I wonder what you want readers to take away from this book?

CYNTHIA – Well, you know, I wrote it for, kind of two primary audiences. One is people in the medical community, so that they could see, this is what families go through, and hope that they have a little bit more compassion when they’re dealing with families like this, and that the other families won’t have the same experience that I had, where they’re basically saying, Okay, here’s your brain injured husband, see you later. You know, you figure it out. I mean, it would be so nice if people in the medical community would at least acknowledge what families are going through. And maybe you know, once in a while, ask – like, How are you dealing with this? And how can we, in the medical community, be of help to you? To the families, and not just the patient.

CYNTHIA – And the other audience, was for other caregivers, because as I was going through this, it was a very lonely experience. And I felt guilt every time I didn’t want to be in this role. And I’d always think, I am not as kind as other caregivers, because I have these moments where I just resisted this role and wished that it would be over. But I think all caregivers feel that way, you know? And I had looked for a book like this when this happened to my husband, because I wanted to know, well, how do families deal with this? How do they get the strength to just keep going? Or, you know, do you just shut yourself off to the world?

JANA – Yeah, and it’s a very specific injury. I haven’t read a book like this before. And I’ve read a lot of books for the interviews I’ve done. And it was a really worthwhile endeavor. And it was very, very well written. So I want to just say I really enjoyed it. We’ve been speaking with author Cynthia Lim about her book, “Wherever You Are: A Memoir of Love, Marriage and Brain Injury.” This book pulls you in right from the start. It’s accessible, it’s well-written and it doesn’t pull any punches. In other words, it’s real. We’re going to have links on the Agewyz website to Cynthia’s book, her website and her Facebook page so you can connect with her and learn more about her work. Cynthia, thank you so much for being on the show. And thank you for writing this book. I mean it sincerely when I say I truly enjoyed it, and I want everyone to go out and buy it. “Wherever You Are: A Memoir of Love, Marriage and Brain Injury.” Thank you, Cynthia.

CYNTHIA – Thank you so much.