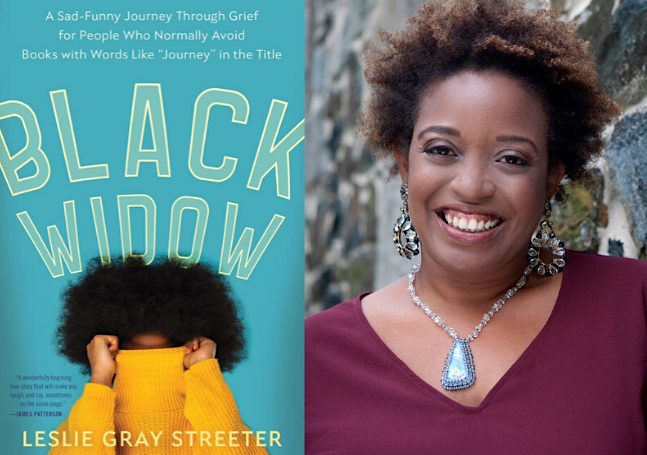

Veteran writer Leslie Gray Streeter established a loyal readership through her Palm Beach Post column, “That Girl.” Now a general entertainment columnist at the Post, her writing for the newspaper began in the early 2000s and eventually included mentions of Scott Zervitz, referred to in Leslie’s column as The Gentleman Friend when she and Scott were dating, and The Mister after they married. Baltimore natives who went to the same high school but didn’t know each other well at the time, Leslie and Scott had re-met after 20 years and become soul mates for life. But tragedy struck in 2015, when 44-year-old Scott died of a heart attack and Leslie became a widow. By her own admission, she was not cut out for the role. Five years after Scott’s death, Leslie shares her moving love story and twisty path through grief and loss toward healing in her new memoir, Black Widow: A Sad-Funny Journey Through Grief for People Who Normally Avoid Books with Words Like “Journey” in the Title. On the show and in print, Leslie has a few things to say about grief. Aging, too. Black Widow will be published March 10, 2020 by Little, Brown.

Buy Black Widow: Amazon | Barnes and Noble

Leslie’s website: Leslie Gray Streeter

Columns in the Palm Beach Post (from the archives): PB Post

Leslie’s husband, Scott, died on July 29, 2015. Later that year, her editors at the Palm Beach Post persuaded her to share some of the many condolence letters she received from readers of her column.

INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT:

JANA PANARITES (HOST) – In July of 2015, Palm Beach Post entertainment columnist Leslie Gray Streeter was married and in the process of adopting a baby boy with her husband and love of her life, Scott Zervitz, when tragedy struck. “In about 90 frantic seconds,” as Leslie wrote, her 44-year-old husband Scott died of a heart attack, and Leslie became a widow. Her incredible love story and the aftermath of Scott’s death is the subject of Leslie’s memoir, “Black Widow: A Sad-Funny Journey Through Grief for People Who Normally Avoid Books with Words Like “Journey” in the Title”. Besides her popular column for the Palm Beach Post, Leslie’s writing has been featured in the Miami Herald, Modern Loss and elsewhere. She’s also written for the stage. Her funny and smart Christmas play, “The Gift of the Mad Guy” has been featured by Annapolis, Maryland’s Building Better People Productions and others. But today Leslie is here to talk about her memoir, Black Widow. Leslie Gray Streeter, welcome to the The Agewyz Podcast.

LESLIE – Thank you.

JANA – Leslie, before we get into the book, I want to talk a little bit about your background. In your book you wrote, “so much of my story might be considered all-American, if not for my high melanin level,” which is such a provocative statement, in a good way. Tell us about growing up in what you’ve called hood-adjacent Baltimore – and your parents and your twin sister.

LESLIE – Well, I grew up in Baltimore City. As you mentioned, I do have a twin sister, Lynne, it’s just the two of us, so people would always ask, what’s it like to be a twin? And they were incredibly disappointed all the time by my answer because, as I say, in the book, we’re not psychic or in porn. So it’s just, you know, we weren’t that interesting. I think that people are like, Well, what do you have to compare it to? Which is nothing, because I only have a twin, I don’t have any other siblings. So I have no other sibling relationship to compare it to. So it was just kind of like being normal.

LESLIE – I mean I will say that it’s sort of, and no one wants to hear this because it sounds very psychological, but the fact that – I understand that the two of us were raised by the same people, at the same time, with the same parents, at the same time in their lives. So it’s not like my mother and her youngest sister. There were five of them, and my mother is 14 years older than her youngest sister. So her, even though she was raised by the same parents, they had completely different experiences of growing up in that family because of everything. And my sister and I had the same experience at the same time, which I think is kind of remarkable, because we remember stuff the same, or close to the same, as much as any two people remember something the same. Or there’s no, Oh, Mom and Dad were so tired by the time they got to me, they were just like, just take this stovetop stuffing and shut up, kind of thing. So we both got the same, fairly young and energetic first time parents. And as my mother said, she didn’t always do everything right, but you know, they did it from the heart. You know, they were just very enthusiastic about being parents in this adventure, and even when there wasn’t enough money or they didn’t know what they were doing, they were like, Ah, it’s what you do. So I think it’s different from – my parents were 24 when we were born. I was 41 when we brought Brooks home, so…

JANA – Right. Brooks is, for listeners, Leslie’s adopted son.

LESLIE – Yes. Well, he’s – I just say, “my son.”

JANA – Your son. Yeah, that’s a good point.

LESLIE – I mean, he’s my son, who is adopted. But you don’t say-

JANA – that is such a good point.

LESLIE – It’s something that people who are not in adoption or surrounded by adoption, just don’t know. And it’s not malicious. It’s not trying to get it wrong. It’s just – you don’t know, so… and that’s a point that people make, particularly if you have natural children, and people say, Well, these are their children and their adopted son. It’s like, that’s stupid.

JANA – Yeah. So your parents sound super cool. You described living in Saudi Arabia for one and a half years as a “great adventure.” And it really influenced your becoming a writer. I wonder if you could reflect on that.

LESLIE – Well, it’s just, I felt like I was going to be a writer. I didn’t know what the word for that was. Since I was little, I think, that I was good at creating stories, I was good at like being creative. And you when you’re 11, you don’t think I’m going to do whatever for a living, because you don’t know what it means because you don’t pay for anything. But you know, you’re just like, I could do anything. Because my son any other day wants to be a firefighter. Every once a while he wants to be a Jedi. You know, none of these are things that he’s driven to do because of what they pay. It just seems like they’re cool things to do.

LESLIE – So I think that doing something like that, but moving where we did at the time that we did, and to do it only for, you know, one and a half school years and come right back, was not only jarring, but it really makes you think, Who am I, and what am I going to be? And isn’t this a good thing to tell stories about? Isn’t this a good thing to write about? And I did. And I started just, like – I would write stuff sometimes for me. Also, I think that that’s around the age that I started writing for my projects.

LESLIE – Like when I was in eighth grade, people would say, Oh, I’m going to do a history project where I make a diorama of the Revolutionary War out of marshmallows, or whatever. And I was like, I’m going to write a play. And I would write a play. And I would do it the night before because I procrastinate, and it would take me all night. But I would hand write on notebook paper a play, and then I would staple it together, draw some sort of cover and hand it in, and I always got A’s on those things. Because they were good, for an eighth-grader, I guess. And because I think that possibilities were kind of open and I didn’t know how to do anything else. (laughs) I wasn’t good at anything else.

JANA – So Leslie, you met Scott – actually, you and Scott went to high school together –

LESLIE – yes.

JANA – and you tell this marvelous story about how you guys reconnected. Tell that, briefly.

LESLIE – Well, basically, everyone gets together on Facebook now, so our class was planning what was then our 20th reunion. We just had our 30th. But back in the beginning of 2008 we were planning our reunion for the next year, and we both realized that we had a connection to South Florida. I was living here. He had lived here and had gone back to Baltimore briefly. And he emailed me when he got connected with me and said, Hey, I’m gonna be back down at some point. You want to have a drink? You know, I wasn’t into it. I was just like, Okay. And then I went back to whatever I was doing. I hadn’t seen him in 20 years.

LESLIE – And then we went to Boston’s on the Beach in Del Ray, and I was sitting at the bar, having a crab soup – that’s before I was vegan – and having a glass of wine. And I looked up and there he was, and I thought, Oh, OK. And his eyes are so cute. He had really thick glasses, but you could see his eyes. And I remember from high school that he really pretty eyes. And I thought, Oh, okay, there you go. And then he said, Well, I’m gonna be here for a little bit, but I’ll give you a call. And I thought, Okay, great. And I thought, Wait, I think I want him to give me a call, which once again, I had not expected, but it just kind of went from there. He kind of spoke to my better judgment. Because as I mention in the book, I have had bad taste in men at some points in my life, and he was a good choice – which is why I was like, Why am I doing this? This makes sense.

JANA – Well, you also wrote he’s really hard not to like.

LESLIE – He really, really was.

JANA – Leslie, I wonder if you could reflect on introducing Scott to your extended family. Your family’s so interesting.

LESLIE – Well, it’s just – it’s the kind of thing that, I can’t really describe them to people who don’t have imagination. So it’s kind of like – and I do everything by movie references or TV references – there’s a definite Huxtable thing to my family. If people are newer TV watchers, my family person can be very much like Randall, the black son on “This Is Us.” We’re very educated. We don’t suffer fools gladly. And if we have to – I’ve never had to be in a fight, but I’ve made people believe that I could, if they mess with me. I can’t. I can’t fight. But you know, it’s that kind of thing.

LESLIE – Really cool people. Like, everyone was very raised in the church, very sort of specific ideas about things. Like I said, when they met Scott they weren’t shocked. They were just like, Oh, who’s this? And I had not had a whole lot of relationships that were important enough for them to meet someone. It had been years since I had actually introduced them to anybody. So they were like, Oh, okay. I mean, my parents liked him. Immediately.

LESLIE – My mother said that she was not sure how serious it was, because I was kind of playing it off. And she had come to visit and she called my dad back in Little Rock and said, This guy’s in love with your daughter. And he was like, Who? And she was like, I’m just telling you, be ready for it. It’s a thing. And then, like months later, he and I and then my sister and her then-boyfriend, who she then married the year that we got married, all went up to Little Rock and did the meet-the-parents thing. And it was really cool. We had such a good time. I love the pictures from that time. We went to the Clinton Library and Scott took pictures behind the Bill Clinton desk and stuff. It was great.

JANA – Leslie, this book is really jarring in a way because it really grabs you right away. It begins the day after Scott died, when you’re arranging for his burial-

LESLIE -yes.

JANA -you’re listening to a pitch from a cemetery salesman. The tone is set immediately with your wit. This is a quote. Here you are, “a black Baptist woman planning a Jewish funeral for her white husband.” So tell us what happened.

LESLIE – Well, basically we had gone with extended family members to have dinner the night before in Boca, and came back, and he hadn’t been feeling well, but not like in an alarming way. I mean I was – at one point I was like, Should we go to the doctor or something? He kept saying, I really don’t feel well. And you know, men don’t always complain. Either they complain like babies, or they don’t complain at all. So I was like, are you okay? And he’s like, No, I’m fine. And he took – I remember, I can see him now throwing – he had this stupid habit of like taking pills with no water. He took some aspirin or something, like, threw it down and like I said, it was disgusting.

LESLIE – But the next morning around three, he got up to go to the bathroom. And I was getting up around 4, 4:30. I had a story that was due that day, and it was easier to work before the baby got up. So he got up, and he said, Hey, do you want to fool around? And I was like, Sure. So we were just kissing and stuff, and then he told me that something was wrong and I turned the light on. And he was clearly in distress.

LESLIE – And I go over this a lot. The writing has been helpful, because it’s helped me sort of – not so much remember, but it’s helped me kind of piece things together. But it’s hard exactly what to say, because I was in shock. And anyone would be in shock. I don’t know how people give testimony about things like this, because you would have to get something wrong. I mean, I think that our bodies release chemicals that keep you in shock, you know. So. Having said that, I just remember that his head shook and he passed out. I think he died then. I thought he had just passed out. So I grabbed the phone, called 911. It seemed like it took forever. He was pronounced later at the hospital. But like I said, I don’t know. And they weren’t nice. But they weren’t awful.

JANA – Yeah. There were some awkward moments there.

LESLIE – Yes.

JANA – Yeah, there’s so much going on in this book. And it’s so interesting because it’s infused with pop culture references, from “Sex and the City” to “Law and Order” and “Titanic.” And this framing of grief in pop culture is really new, for me. But of course, it’s totally natural for you because it’s what you’ve been, you’ve been writing about pop culture forever –

(overlapping)

LESLIE – that’s what I write about.

JANA – Exactly.

LESLIE – It’s kind of like, I’ve read books that are not sports-related by books who were sports guys, and they write- their references are sports. Or historians write in historical references, not necessarily framing, but when they make a reference, that’s what it is. And what I know is pop culture and movies and music and stuff like that. So I tend to speak in those things because it’s sort of like easy references.

LESLIE – Also, the older I get – I’m in my late-40s – I find that sometimes if you use kind of a general reference, it’s something that people both older and younger will get. When I was first editing it they were references I thought, is anyone going to get this? And I thought, people my age will get it. And really that’s who I’m writing to. I mean, I think – I want it to be for everyone. And I don’t think that a Sheila E reference is really going to throw anybody off.

JANA – Yeah. In Black Widow, Leslie, you write about being, quote, forcibly cut out of your old life on returning from Saudi Arabia, and having no real choice but to find yourself a new one. I thought this was interesting because it made me think about how you were forcibly cut out of your old life after Scott’s death.

LESLIE – Yeah, man. That’s a theme, right?

JANA – Yeah. I wonder if you can you talk about that.

LESLIE – I think in some ways, all of us, anytime there is a loss – like, I know that you have lost a parent – or anytime that there is a move… a loss is something – you move sometimes because you want to, so it wasn’t a forced changing. But when a parent dies, whether you lived with them or not, that changes. You’re one step closer to death. My dad died in 2012, and that part of my life, of having two parents, was over. And that’s the thing that happened to me. And Scott’s death happened to me. And I say that, not in like a gross, selfish way, because when you make someone’s death about you, but he’s not here to have it be about him. So it’s – basically, just to say that death ends things. Death ends possibilities.

LESLIE – There’s a conversation in the book I have with a woman who was comparing her divorce to my widowhood. And I say to her, basically, that the difference is that her husband, even if she’s not interested in ever being married to him again, or being romantically involved with him again, he has possibilities of changing his relationships with other people or becoming a better person or whatever. And death ends that possibility, because that person’s not just dead to you. They’re dead. And you didn’t choose it. I didn’t choose it.

LESLIE – And I know that – I don’t compare my relationship to other people’s relationships, because I know that, like, for instance, my friends who are divorced – yes, their former spouses are still alive, but they sometimes have to see them with their new girlfriends on Facebook. You know, that ain’t fun. And that’s something I know I don’t have to do. Once again, it’s not better or worse, it’s just different. And there’s no real comparison to it.

LESLIE – Because once again, divorce happens because somebody doesn’t want to be married anymore. And that didn’t happen in my marriage. We both wanted to still be married, just one of us died. So I think that both of those situations – both having moved against my will at eleven, and being widowed at 44, I think, do have the end result of necessary resilience, and a necessity to figure it out. Because it is what it is, and it was what it was and remains what it is. And you can either crumble under the weight of it, or you can figure out what to do about it.

JANA – Hmm. So Leslie, you’ve written about some of the things that people have said and how people respond to people who are grieving. I wonder if you could talk about what you appreciated hearing from people, and what you did not really appreciate hearing.

LESLIE – That is truly the question that I get from people when I speak outside of grief situations. Because nobody wants to be the bad person. Nobody wants to say the wrong thing. And 98% of the time, even when people screw up, they really mean well. They aren’t thinking.

LESLIE – What I like – and I’ve had some people not like this – what I like is “sorry for your loss.” I’ve heard that there are people who don’t like it because it seems pat. I’m not sure what else you’re supposed to say. But there are people for instance, who say that even saying, “let me know what I can do” is bad because it puts pressure on the grieving person to have to think of something. because now the need is put on them to make you useful in the situation, which isn’t fair. Because often, what I like to do is call the designated person, whether it’s a sister or a mother or, you know, a spouse or whoever it is, this is the person that’s grieving, and say, what do they need? Because by that point that person is a little removed, even though they might still be grieving but they’re the point person, so that person is like coordinating bringing over the chicken. Or, you know, people called my sister.

LESLIE – My sister was down here in hours. You know, I think we got back from the ER maybe around 6:30[am], and I think my sister was in my living room by 11 o’clock, from Baltimore. So, she woke her husband up and said this happened, hand me the credit card, I’m going to see my sister. So she became the point person, so people just showed up at my house, magically, by plane and train and car and stuff, because they would call my sister. Because I think Lynne sent an email out and said, This is what happened, I’m really sorry I don’t have a lot of time to ease you into it, here’s what you want to do. And so if you’re coming down, call me. If you need a ride from the airport, call me. If you need to figure out on what schedule people are delivering stuff to the house, call me. And so that long answer is to say, check with someone else.

LESLIE – I know I do not like – even as a person who is spiritual and considers herself religious – I don’t like “they’re in a better place”…”they’re with God now,” because first of all, you don’t know what that person believes. You don’t know if the person- if either the grieving person or the person who died, believed that. You don’t know the pain that they were in. You don’t know anything.

LESLIE – Also, I didn’t like anything that suggested that there was a better place for him than sitting in my house. Because that’s where he was supposed to be. And it wasn’t like he’d been ill and in pain, or in hospice or on life support for a long time. It was: he was here and then he wasn’t. So, saying Scott has completed his cycle around the sun was so dumb to me, because it was trying to make philosophical sense over something that didn’t make any sense. And it was designed – it’s the kind of phrase that’s designed to make the person who says it sound smart. And I don’t like it. (both laugh) So, you know. So it’s stuff like that.

LESLIE – I think that sometimes people want to listen. And I think that if you ask a grieving person – and you know this – how they’re feeling, be prepared for them to tell you. Because sometimes they won’t, but sometimes if you’re a good enough friend or family member or whatever, it’s just the day that they need to talk about it. And I would say, Do you really want to know? If you’re just asking to be polite, I’m going to spare us both the uncomfortableness and say, Great, better than yesterday, thank you.

JANA – Move along, nothing here to see.

LESLIE -Move along, nothing here to see. And I think that – and once again, you understand this as a person who has been through this kind of thing – anything that makes the grieving person feel that they have to do anything, or that they’re somehow responsible for how you’re doing, or that they have any responsibility to make you feel better. When my dad died, I remember specific people I didn’t want to talk to, because I knew that they were going to be, Oh, no!!! No!!! And I didn’t have the energy.

LESLIE – As I said to a friend, who was very upset with me because I hadn’t told her that he was sick again – it was when he was sick again – and she goes, Why didn’t you tell me? And I said, Because I know, as much as I love you, that you were going to be so over-the-top, that I was going to have to feel like I had to help you through my grief about my dad dying. And that’s sort of the thing. And that was before he had even died, and way before Scott had died. But it was the beginning of that feeling of being able to articulate in a perhaps brutal but very real and vital way, I cannot be responsible for you. And, I am the person central in this grief. So how you can help me is by listening to me when I tell you how to help me. Don’t help me the way you want to help me. Help me the way I tell you what I need.

JANA – Mm-hmm. Leslie, Scott was a regular in your Palm Beach Post column, which was, “That Girl.” He appeared in photos, he was initially referred to as The Gentleman Friend and later, The Mister. Somehow you managed to write about his death in the Post less than three months after he died. I wondered how readers – who you refer to as your “other village” – helped you through this period?

LESLIE – Readers were, and I shouldn’t say surprisingly but, you know, the world sucks sometimes, so you never know. I really expected more ignorance in the first couple months. And I didn’t get it, or it was sent to someone who kept it away from me. So people were pretty cool. This area, obviously, has a lot of older people in it. So I had many, many widows, many, many widowed people reach out to me. Some people who were married and would say, you know, I understand it. Some people who were not married and say, Is it okay for me to call myself a widow? I’d say, Of course it is – shut up. (laughs) You know. Or couples who were gay, or couples who, like, “It’s Complicated” was made for them. You know, people who had been married and divorced and married again, and it was a whole situation.

LESLIE – I know a couple who was estranged when he died, but it didn’t mean that she didn’t have all the complicated feelings about it. And so when I would talk to those people, and it would start with conversation, those people it was OK to kind of be griefy with, because they had their own and they understood, and they weren’t saying anything to me or trying to get me to feel anything that they had not wanted to feel in that very specific situation. So… and it’s been almost five years.

LESLIE – I ran into a woman recently who I know, who lost her partner several months ago. And I ran into her in public, and we just cried. We just cried. I hadn’t seen her since then. But we both knew what we were feeling. And we just cried. And I think that now I’m at the point where what’s helping me through, is being able to help other people, which is one of the reasons I wrote the book. But in the initial time, just people saying, I’m so sorry. Or people saying, Here’s a picture of my husband, he died a year ago, you would have liked him, whatever. Or just people like showing up. Like, I write about in the book, my friend Libby just showing up at my house and saying, I’m on the way to your house, get dressed. And I’d be like, I don’t want to go. She’s like, No. In the Uber. Can’t stop the Uber. Get in the Uber. And I’m like, No! But – and those are people who I’m very close to, and they knew what I needed. And they wouldn’t have made me stay out for like five hours. Sometimes it was just like, driving around the block. But just checking in.

JANA – Mm-hmm. I thought it was really brave of you to post the video on the Palm Beach Post website, where you read aloud some of the condolence notes you read. That must have been tough, but in a way, it probably helped you heal.

LESLIE – It really was. I mean, when they first said it to me, my – I was like, No. Nope!

JANA – That wasn’t your idea.

LESLIE – No. It was not- noooo… it was not my idea.

JANA – So explain what we’re talking about, for people who aren’t familiar, what happened there.

LESLIE – There was this, eventually, incredibly lovely, lovely video that was so thoughtful. And once again, the people that I work with are so talented, and all of them1 were watching me, try not to disintegrate before their eyes. So it was really lovely, this video of me reading out loud some of the condolence letters that I had gotten. And once again, it was not my idea. What I said was, I want to find some way to explain what these people have meant to me. And they said, Why don’t you read the letters? I was like, No! And then I went, Why not? And I went, OK, you’re right. And breathing through it – and so many people said, again, people who were widowed, said to me, Oh my gosh, that was helpful to me. Oh my gosh, you said things out loud that I had not been able to say out loud about my loss. So, yeah.

JANA – Mm-hmm. That’s really cool. One of the things that was so moving was to read, throughout the book, your ongoing struggle with what you were going to tell your son. And how hard it was to say the words “daddy is dead.” On the day of Scott’s funeral, you took Brooks to the doctor, and you asked her, What can I do to help Brooks with what’s going on? And the doctor gave you some good advice. Maybe you could share that. And then three months later.

LESLIE – Yeah, basically what I said was, By the way, can I get out of going to the funeral? Which was, no.

JANA – On the day of the funeral.

LESLIE – That was on the day of the funeral. I was like, Can we go? No. OK. So. And then she was like, He’s not yet two. Therapy isn’t going to be helpful to him. He doesn’t really know what’s going on. But you need to be solid. You need to get therapy, you need to stay healthy in every way, because he’ll get his cues to what normal is from you. He can read your panic, he can read your depression, he can read your shock. And of course you have those things right now. But you got to work on them, because otherwise he will internalize those things. And she was right. You know, and I think that going to therapy, and staying healthy, and trying to make sure that I’m around for as long as possible, and positive, and surrounded by positive people, and just doing things that are helpful to myself and to him, I think that that has been great, because he’s a very well-adjusted little boy.

JANA – And how old is he now? Six?

LESLIE – He’s six.

JANA – Brooks. So, we have all these ideas about how we should age, how we will age, what our lives will look like when we’re older. And we plan accordingly. I wonder how your ideas about aging have changed if at all since Scott’s death.

LESLIE – Oh my goodness. My – first of all, I have no patience, no patience, for people who whine about getting older, because my husband didn’t get to. So, screw you. I don’t care about your wrinkles. I don’t care about your – it’s harder for you to run now, and you can’t keep up with your kids. Shut up. You’re breathing. You’re breathing. I don’t have any patience for it. I have friends who are younger than me, who go, I’m going to be 40 (whiny). I’m like, I’m gonna be 50. You’re still breathing – shut it.

LESLIE – And it’s OK to say, I didn’t expect this wrinkle. Or to laugh about your muffin top, or to laugh about falling asleep at eight o’clock when you know, 15 years ago, people were like, We’re gonna go out at nine and now I’m like, I’m in the house by nine. It’s okay to joke about that. And obviously there are people who have anxiety about things. I think a lot of anxiety about aging is built around our parents and how we saw them age, or how we’re seeing them age. So I know that this is not for most people a trite thing.

LESLIE – But I am in love with the idea of aging. Because I feel like I owe it to my son, and I owe it to my husband, to age. And to age as well as I can, to age as enthusiastically as I can, to be as in love with my body as I can be, to be as in love with whatever’s going on with like, the weird like laugh lines around my eyes, and my slow running and all that other stuff. Because I’m not who I was when I was 35. I’m a better person than I was when I was 35. I’m better than I was at 44. And a lot of that, I think, is just aging. And a lot of it is – I think it’s just that I’ve learned a lot, but I’ve learned mostly to never take life for granted. So to complain about stupid crap, it’s like just buying the wig and move on. (laughter)

JANA – Well, people frame their grief in different ways, and of course true to your storytelling roots you frame it as almost like a Joseph Campbell myth where you- the hero goes into –

LESLIE – I love that.

JANA – you know, the unknown, your life is tested by a cataclysmic event – Scott’s death – and you talk about the tremors of grief that you experienced that are, of course, universal. I wonder if you can could offer some advice for surviving the tremors of grief, for other folks.

LESLIE – Oh, first of all, I have to say, I have never been referred to in any sort of reference to Joseph Campbell. So that is super cool. I cannot imagine – and I hope this is not too provocative – that Joseph Campbell, imagined that he would ever be compared to a black woman. Think about it.

JANA – True.

LESLIE – Think about it. Anyway. I just love that. People go, Oh, you could be like Lewis and Clarke. I’m like, No, not at all. (laughs) No, not a fit. I loved “Heart of Darkness” though. I read it in high school. And it’s interesting to allow yourself to think of yourself – and in the title of book I say, a journey for people who don’t usually pick up books with words like journey in the title, because I think the word journey can be super obnoxious. I think depending on what it is, it can be super self-referential. It can be super patting yourself on the back: Oh, look at me. This is my journey. I’m so important. I have a journey. I’m a hero. Here’s my arc. You know, here’s the people to sing my praises. Yuuukkk. You know, I just – echhh.

LESLIE – But. Having said that, there is, I guess, a hero’s arc to most people’s stories. And I think that in this, the hero has no idea what she’s doing. Basically, she’s like Robinson Crusoe. She’s kind of dropped off on a frickin’ island, like – deal with it! You know, and her journey is trying not to die and get rescued. And I think sometimes you have to rescue yourself. I think that the advice I would give people is to know that it’s coming.

LESLIE – I just recorded the audio book, and one of the things that I read out loud, that was like, Oh, this resonates so much, still, is that you have the understanding that in the middle of grief, that after the funeral, it’s not going to stop being awful. Because the funeral doesn’t end anything. The funeral just ends that part of it. And that you’ve just dipped your toe into the pool of awful. You’re just dipping your toe in. You haven’t even immersed yourself all the way into what life means without that person. And not just the emotions, but it’s – the paperwork, and remembering you can’t call them to tell them about “Law and Order,” and all that stuff. And that you will forever be without that person as long as you’re on this earth. I don’t want to be rude and say buckle up, but buckle up. Because it is a long process. And I do not grieve Scott in the same way that I did in the beginning, because I couldn’t. You couldn’t survive. You would run out of air and tears. You know, you can’t do it. And your body, and therapy, and psyche and everything moves you through different stages.

LESLIE – I also would tell people that the stages of grief were never meant to be cyclical, and they weren’t really about death. What they were about, the Elisabeth Kubler Ross stages, were about the acceptance of people who had found out that they had a fatal disease. That’s what those were about. And they were never meant to be in order. So people go, Well, now I’m in acceptance. And now I’m in denial. And now I’m in anger. It’s like, I was in all of those things the day he died. Every single one of them.

LESLIE – And one of the early drafts of the book says, that grief is not a ladder. It’s more like a funhouse that lost its brakes, and you’re just kind of like zipping around and you fall to the basement, and then something catapults you up and you go back to the other one you thought you’d already been through? Just to expect that it’s going to be hard. It’s also to expect that some people are not going to understand or approve of the way that you are grieving. And some of them may be your parents, or your spouse if – depending on who you’re grieving – the people closest to you might want you to just get over it, and move on. Some people may want you to be in that performative grief stage to prove you’re still grieving for longer than you want to be, or longer than you actually are. And you got to screw those people and do what you got to do.

LESLIE – Understand that everyone around you is grieving. Scott’s family’s grief was different than mine, but it was still valid. And I couldn’t say my grief is more important than yours, because that’s not fair. And it’s not a competition. It’s not a competition. And the boldest (?) thing I would say is, it ties back to what you asked me before about what people say to you, is that there will be days when you feel awesome, and someone will walk up to you, and without understanding that they’re doing it, punch you right back where you were and go, Oh…. I’m going to go back and cry now. And it’s going to happen. It will happen less over time.

LESLIE – But also, I mean, I remember going to a cocktail party with this woman who didn’t know. So I used to see her – we saw each other at cocktail parties. She was seasonal. So I saw her at a party, and she goes, Oh my gosh, where’s your husband? And everyone else in the room but her knew. And it got super quiet.

JANA – Wow.

LESLIE – And I had to tell her. That was also the party that when I left, I was literally holding a pizza, waiting for my car, and the valet who was surprised that a black person was waiting – it was more logical to him that I was delivering him a pizza than I was waiting for my car. I was wearing a dress with a purse on. I go, I’m wearing a purse! I’m 45! How many 45-year-old women holding purses, wearing dresses, deliver pizza?

JANA – Oh my god.

LESLIE – It just – it was so funny. Because that happened at the end of that cocktail party. So I was like, Thank You, Jesus. I was given something funny to laugh about. Because it was funny. Like, goofy, stupid. And I was like, Get my car, kid. And the other guy ended up getting a laugh. The guy laughed, and he goes, That was bad. That was bad. And I’m like, Yes it was. (laughs) Yes, it was.

JANA – Yeah, you think?

LESLIE – It was like, Tell your friend Gary he’s a moron. But it was funny.

JANA – Yeah. Leslie, how has your writing changed since Scott’s death, if at all?

LESLIE – I think that when I deal with hard stuff, I am much less likely to pull punches. I never really did. But you know, my style is, like, lots of words, lots of words, a thing. And I think that (a) I am older, I don’t have time for that anymore. But I think that also I’ve become a lot more concise because I know emotionally, I think, how to get to the heart of a thing faster than I used to. Honestly, I think that I’ve become a better writer, but I think that hopefully, as long as my brain works, I hope I continue to. I hope I continue to become a better writer, and funnier in an organic way that’s not trying too hard. There was a review that said they thought that sometimes the humor was forced. And it’s not. But they don’t know me, and also people aren’t used to people writing funny things about grief, so I can understand. That’s valid, for them to feel that way.

JANA – Right. Tell us about Camp Widow, for folks who don’t know about this. It sounds like a marvelous thing. Is it a national event?

LESLIE – It is international now. Camp Widow is a program of an organization called Soaring Spirits International, that’s based in San Diego. And it was founded by a widow, Michele Neff Fernandez, who’s amazing. Michele is this person who thought, I have all these feelings. Other people must have these feelings. How do I connect to those people?

LESLIE – And it’s become a series not only of around the world Soaring Spirits communities, where people have groups and meetups and talk, and suggest therapists and stuff, but Camp Widow happens primarily in Tampa, San Diego and Toronto. And now there’s some pop-ups. One’s in Australia, where her second husband is from. That’s really cool, because he started this community even though he is not a widowed person. And he lives in San Diego now. His influence has started that there. Basically, it’s three days – it’s usually, it’s a Friday, Saturday and Sunday of workshops and a dinner and parties and rituals. And down here in Tampa where it’s warm in March, when they have it, there’s a 5-K, and just opportunities to talk to people.

LESLIE – There’s something about being in a room full of people where you’re not weird. I mean, you’re still weird, but where the identifying detail of your life is not weird, because everyone else has it too. And you just sit down and talk and say, so what happened to you? When was your loss? And everyone has a loss. Because there’s no one who’s gonna go, Oh, that’s weird. And there’s some people aren’t really ready to talk about it. There’s people who’ve been widowed 10 years and people who’ve been widowed like a month, and they hear about this thing, and they don’t know what they need at the moment. But to go, I need to go.

JANA – And there’s one coming up probably, right? Are you speaking at it?

LESLIE – There’s one coming up. I am. I am signing some books, doing a couple workshops. I was a keynote speaker in Toronto, in November, which was really cool. And my mom got to go, which was neat.

JANA – Oh, that’s great.

LESLIE – Because she’s widowed as well. And we’re going to go again, as well, in Tampa – to Tampa, in March, which is a couple weeks after the book comes out. So that’ll be a neat situation, too. And all these people that have known me forever, I’ve been talking about this book for years and now it’s actually here, which is really cool to be able to say, Here’s the thing! And they’re like, Oh, you didn’t make it up. So.

JANA – Leslie, you sort of alluded to this earlier but I’ll ask it formally. What do you want readers to take away from this book?

LESLIE – I want people to understand that grief is normal. We think in this society, we’re so smart, that we can talk about sex and we can talk about our bowel movements and our sexual dysfunction and whatever it is – and our aging in our knees. But grief is a thing that happens to everybody. And there are no age restrictions for it. You can’t stop it. Everyone is going to lose somebody. And it’s a thing that’s so hard to talk about. So what I want to do more than anything, is to get people to understand, your grief is normal, whatever that is. Grieving is normal.

LESLIE – And it is normal not to know what to say. It’s normal not to know how to be. It is normal to react like your world has been cut out from under you because it has. And just being able to talk about it and say the words “I am grieving” is going to make people uncomfortable, and I don’t care. (laughs) I don’t care. I mean I don’t, like, lead with it at parties or anything. But if we’re having the discussion we’re going to have the discussion, you know? And I think that you would be more – you, the proverbial you – would be more helpful to the people in your life if you understood it, and if you didn’t cut them off because it made you uncomfortable, or if you didn’t try to gaslight them into pretending they were OK when they weren’t OK.

JANA – Hm-hmm. Here’s my last question. What’s a good day for you, now?

LESLIE – Most are really great. A good day sometimes is when someone on Facebook will tell me a story about Scott I didn’t know. I love that. There’s a woman I met, Tanya Villaneuva Tepper, who is a 9/11 widow, who is now remarried, and amazing, and she gives really great talks at Camp Widow. And she said that when her fiancé, Sergio, a firefighter in New York who had died on 9/11, that one of the worst things to her was that he wouldn’t make more memories. That his life ended at that moment and he was unable to make new memories. But she found that when she spoke to other people about him, who were new to her and new to him, and told stories, now they had a memory. THEY knew a story. They knew a thing about this guy.

LESLIE – And so, alternately, Scott was like the life of the party, and in college they called him Scotty Z and he was, like, the head of everything. And my sister went to that college – I didn’t – so they knew Lynne, and they knew Scott. So people will email me and go, Did I ever tell you about blah, blah? And I’ll go, No! Put it on Facebook, put it on Facebook. Because I love those stories. Because I love learning new things about the guy that I loved. It’s a gift. What a gift, to have new stuff to know. It’s amazing.

JANA – Mm-hmm. So you have lots of good days.

LESLIE – Most of my days are good at this point. I mean, it’s been almost five years. So. I mean, you have days every once in a while – I mean, we’re coming up on the 10th anniversary of our wedding, on February 28th. So I’m a little more emotional than I usually am. And so there will be days also because the book – I’m talking about things, and I went back to therapy, which is wonderful. We’ve had therapy months ago to prepare for this, and to prepare for the having to talk about it, and have people ask me questions like, you know, be able to reason these things and craft an answer for these things within very little time.

LESLIE – So most days are good, but there’s always going to be… you’re going to hear a song, or you’re going to turn a corner, or you’re going to pick up a thing and go, Oh. And you can’t paper over those things. And I try not to. I try to let myself feel what I’m feeling about those things. But then you kind of go, OK, what can I do with that? You honor the feeling, but I don’t randomly cry really anymore. Or I’m able to laugh long and heartily about stuff. And the release and relief of getting mad is really great, because then you remember that this person was a person, and not a saint, or some person that’s entombed in time. You know, that they were a person, they were human. It pissed you off. And that’s healthy.

JANA – We’ve been speaking with Leslie Gray Streeter, veteran writer and entertainment columnist for the Palm Beach Post and author of a new memoir titled, “Black Widow: A Sad-Funny Journey Through Grief for People Who Normally Avoid Books with Words Like ‘Journey’ in the Title.” “Black Widow” is set to be released on March 10th, and it’s available now for pre-order on Amazon. com and Barnes and Noble, and at your local independent bookseller. All of Leslie’s columns for the Palm Beach Post are available at the newspaper’s website – that’s palmbeachpost.com, and of course be sure to check out Leslie’s website: lesliegraystreeter.com. Leslie, thanks so much for being on the show, and for writing this funny, smart, moving and truly one-of-a-kind book, “Black Widow”. Thanks, Leslie.

LESLIE – Thank you.

Scattered: My Year As An Accidental Caregiver is available in paperback and eBook at

Scattered: My Year As An Accidental Caregiver is available in paperback and eBook at